Hiding in Second Sight

One of the persistent mysteries surrounding that art form that is called the mystery is exactly how to write a good one. Of course, there’s no denying that a command of the English language is essential. So too is the ability to create such engaging characters that we want don’t want the mystery to end. Indeed, the masters, such as Arthur Conan Doyle, G.K. Chesterton, Rex Stout, and Agatha Christie created such enduring characters that we enjoy visiting them again and again regardless of the crime underfoot. And having a victim, either totally sympathetic or entirely loathsome, is important so that we can either enjoy righteous justice being meted out or secretly delight in someone getting what’s coming to him. But foremost is the requirement, agreed to by tacit contract by the writer with the reader, that the detective’s solution be a satisfying explanation with surprises and ‘aha’ moments that nonetheless ties up all the loose ends. As Chesterton puts it, the writer should provide a simple explanation of something that only appears complex; an explanation that doesn’t, itself, need an explanation.

There are several, classic ways that authors employ to add complexity to a mystery, to obscure what’s going on. These include the red herring, in which an event or a set of clues lead nowhere and only serve as dust to cover the real trail. Another classic approach is to provide so many extraneous details, typically by indulging in sumptuous descriptions of surroundings or detailed appearance and behaviors of the characters, that a vital clue is lost amid noise. And, of course, there are accusations of authors who withhold vital clues and omit important details as is hilariously summarized in the final act of the movie Murder by Death.

Omitting vital clues or important information is commonly considered unfair; a bad show which is against the rules of the implicit contract discussed above. And yet, there is a way to omit something from a mystery while still playing fair with the reader. This fair-play omission occurs when the writer leaves out the second of the Three Acts of the Mind thereby leaving out a judgement or predication of the facts already revealed, which any reader with common sense can make for himself but usually doesn’t.

For those unfamiliar with what philosophers mean by the three acts of the mind, a terse summary must suffice. The first act of the mind shows that mental faculty that allows a thing to grasp what is being observed. For example, it is the ability we all possess to look a room and distinguish a chair from the pistol resting on the seat. In the second act of the mind, a predication about some object observed in the first act is made such as the pistol is smoking. The third act of the mind ties the various observations and their corresponding predications together with connective reasoning to conclude something like: since the pistol is still smoking and the cause of death is a bullet wound, the murder must have committed the crime only a short time before.

Omitting the second act of the mind doesn’t violate the contract since it neither steals a simple clue from the reader’s notice nor does it hide a clue in plain sight by requiring the reader to have narrow, specialized knowledge to understand it. Rather, the writer shares information freely but doesn’t spoon feed the proper interpretation, relying, instead on the reader to provide it for himself.

An excellent example of how to omit the second act of the mind and thereby write an engaging mystery is Edgar Allen Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue.

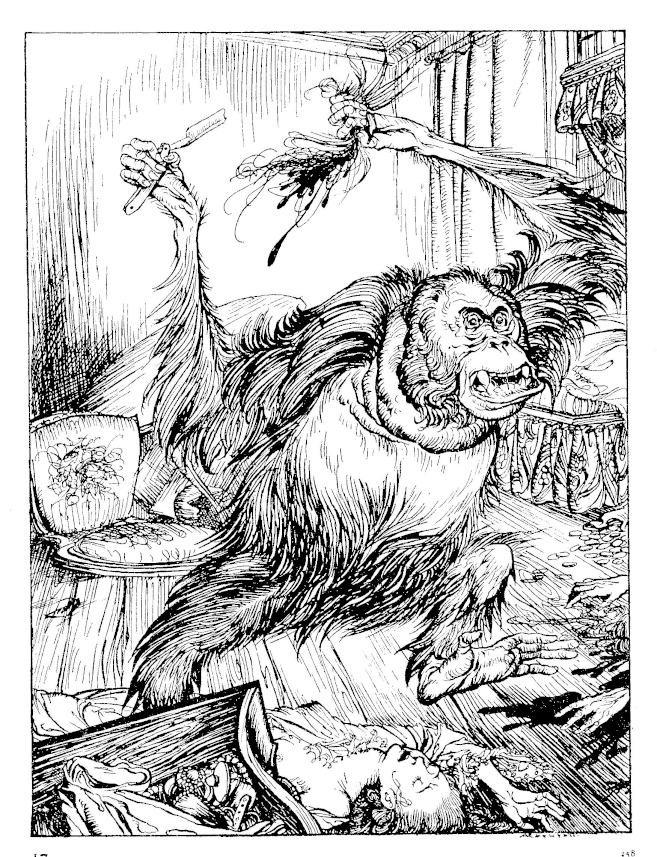

This mystery, told by an unnamed narrator, centers on the horrific deaths of Madame L’Espanaye and her daughter Mademoiselle Camille L’Espanaye. Both victims were “frightfully mutilated” with the mother being essentially decapitated by murderer using nothing more than an ordinary straight razor while the daughter’s battered and strangled corpse was shoved, head-down, up the chimney so far that the body “could not be got down until four or five of the party united their strength.”

Poe makes the mystery even more interesting by proving scores of witnesses who heard the screams of the women as the crime was unfolding. A subset of these followed a gendarme into the house after the latter had forced entry and arrived on the scene, an upper-floor bedroom, in time to find the daughter’s corpse still warm. The door from the hall into the bedroom was locked from the inside, the room itself was in shambles with the furnishings thrown about, and all its window were closed and locked. Each of the witnesses who ascended the house during the murder testified to hearing two voices coming from above in “angry contention.” The first voice was universally agreed to be the gruff voice of a French-speaking male. The second voice, variously described as shrill or harsh, defied classification of the witnesses. A French man thought the voice to be speaking Italian; an English man thought it to be German; a Spaniard thought it English; and so on.

Having laid out the facts, Poe then allows the reader some space before having his detective, C. Auguste Dupin, fill in the gaps. Dupin provides the judgement (i.e., predication) of the facts that serve as the connective tissue between the simple apprehension of the facts (e.g., two voices in angry contention) and the solution of the crime.

Several of the interpretations that Dupin provides us become clear after their revelation but none so arresting as his insight into the inability of none witness to agree on the nationality of the shrill or harsh voice. Poe puts in marvelously in this exchange between the Dupin and the narrator:

Let me now advert – not to the whole testimony respecting these voices – but to what was peculiar in that testimony. Did you observe any thing peculiar about it?”

I remarked that, while all the witnesses agreed in supposing the gruff voice to be that of a Frenchman, there was much disagreement in regard to the shrill, or, as one individual termed it, the harsh voice.

“That was the evidence itself,” said Dupin, “but it was not the peculiarity of the evidence. You have observed nothing distinctive. Yet there was something to be observed. The witnesses, as you remark, agreed about the gruff voice; they were here unanimous. But in regard to the shrill voice, the peculiarity is – not that they disagreed – but that, while an Italian, an Englishman, a Spaniard, a Hollander, and a Frenchman attempted to describe it, each one spoke of it as that of a foreigner.

From this “peculiarity” in the testimony, Dupin supports the conclusion, arrived at deductively through the exercise of the third act of the mind, that the murderer was an orangutan.

This technique is not limited to Poe alone. Consider the notable example found in Some Buried Caesar by Rex Stout. The reader is given all the necessary facts about a bull accused on goring a man to death. Indeed, the reader is just about spoon fed them just after the murder in a manner as plain as they would be presented in the final explanation. Nonetheless, the solution remains surprising for many of us precisely because we don’t provide the correct predication.

While it is likely that host of authors use this technique, whether knowingly or instinctively, it is curious that the explicit connection what makes a satisfying solution to a mystery and the omission of the second act of the mind to ‘hide’ the solution in plain sight seems never to have been made. And that is an omission we hope to correct.