To Winograd or not to Winograd

Since its inception, a common theme that has appeared frequently in this column is the nuances and ambiguities in natural language. There are several reasons for this focus but the two most important ones are that being able to handle linguistic gray areas is a real test for machine intelligence and that by looking at how computer systems struggle with natural language processing we gain a much better appreciation how remarkable the human capacity to speak really is.

Past columns have focused mostly on equivocation is various forms, with an emphasis on humor (Irish Humor, Humorous Hedging, Yogi Berra Logic, and Nuances of Language) and context-specific inference (Teaching a Machine to Ghoti and Aristotle on Whiskey). But the ‘kissing-cousin’ field of the Winograd Schema remained untouched because it had remained unknown. A debt of gratitude is thus owed to Tom Scott for his engaging video The Sentences Computers Can’t Understand, But Humans Can which opened this line of research into natural language processing by machine to me.

When Hector Levesque proposed it in 2011, he designed the Winograd Schema Challenge (WSC) to address perceived deficiencies in the Turing test by presenting a challenge requiring ‘real intelligence’ rather than the application of trickery and brute force. The accusation of trickery apparently particularly into view due to the Eugene Goostman chatbot, a system that portrayed itself as a 13-year old boy from Odesa in the Ukraine, having fooled roughly 30% of the human judges in large Turing Test competition in 2014. To achieve this, the Wikipedia article maintains that the bot used ‘personality quirks and humor to misdirect’, which basically means that the judges were conned by the creators. The idea of a confidence man pulling the wool over someone eyes probably never occurred to Alan Turing nor to the vast majority of computer scientists but anyone who’s seen a phishing attempt is all too familiar with that style of chicanery.

The essence of the WSC is to ask a computer intelligence to resolve a linguistic ambiguity that requires more than just a grammatical understanding of how the language works (syntax) and the meaning of the individual words and phrases (semantics). Sadly the WSC doesn’t focus on equivocation (alas the example below will not be anything more than incidentally humorous) but rather on what linguists call an anaphora, which is the formal meaning attached to an expression whose meaning must be inferred from an earlier part of the sentence, paragraph, etc.

A typical example for an anaphora involves the use of a pronoun in a sentence such as

Here the pronoun ‘him’ is the anaphora and is understood to have John as its antecedent.

The fun of the WSC is in creating sentences in which the antecedent can only be understood contextually as the construction is ambiguous. One of the typically examples used in explaining the challenge reads something like

The question, when posed to a machine, would be to ask if the ‘they’ referred to the councilmen or the protestors. Almost all people would find no ambiguity in that sentence because they would argue that the protestors would be the ones making the ruckus and that the councilmen, either genuinely worried about their constituents or cynically worried about their reputations (or a mix of both), would be the ones to fear what might happen.

Note that the sentence easily adapts itself to other interpretations with only the change of one word. Consider the new sentence

Once again, a vast majority of people would now say that the ‘they’ referred to the protestors because the councilmen would not be in the position to threaten violence (although things may be changing on this front).

The idea here is that the machine would need not just the ability to analyze syntax with a parser and the ability to look up words with a dictionary but it would also need to reason and that reasoning would be broad rather than narrowly focused. Relationships between concepts would be varied and far-ranging with the sentence

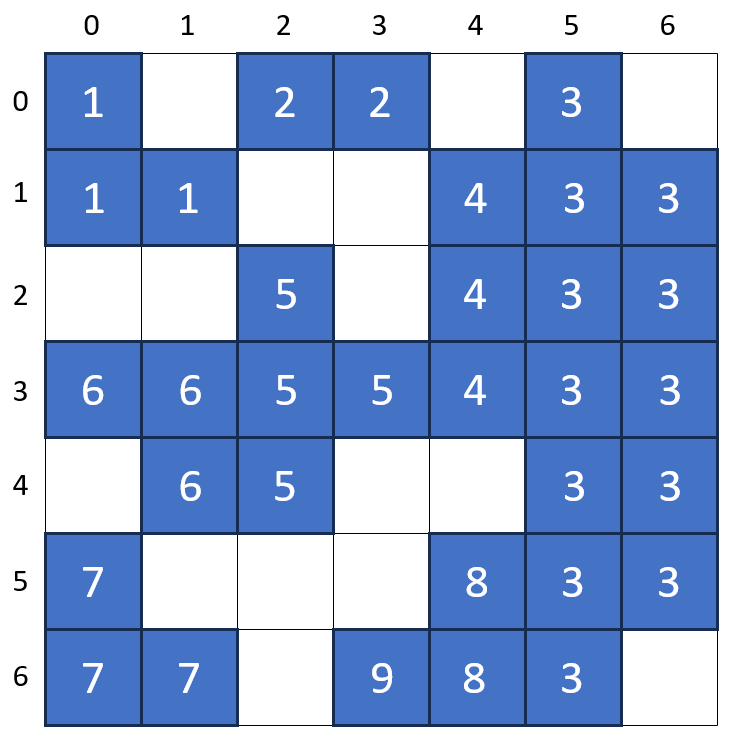

Here the ontology would center on spatial reasoning, the ideas of ‘big’ and ‘little’, and the notion that suitcases usually contain other objects.

These types of ambiguous sentences seem to be part and parcel of day-to-day interactions. For example, the following comes from Book 5 of the Lord of the Rings

This scene, which takes place after Frodo and Sam have managed to escape the tower of Cirith Ungol, is between a large fighter orc and a smaller tracker. Simple rules of syntax might lead the machine to believe that the ‘he’ in the second sentence would have ‘the tracker’ as its antecedent. I doubt any human reader was fooled.

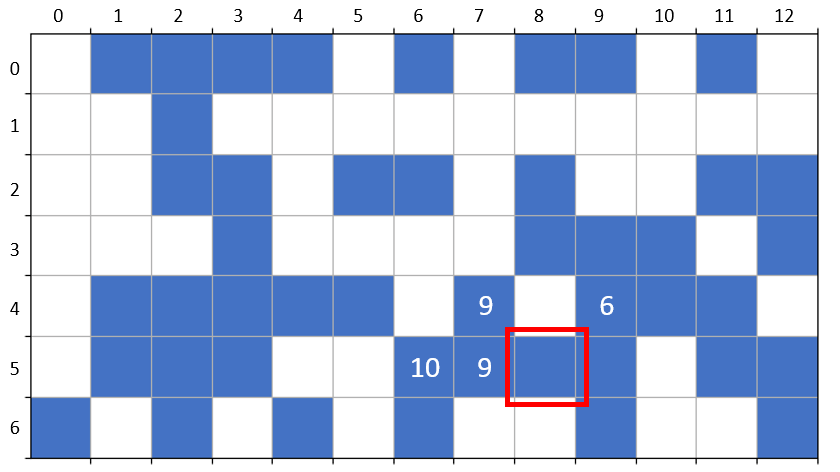

The complexity of the WSC is not limited to only two objects. Consider the following example taken from the Commonsense Reasoning ~ Pronoun Disambiguation Problems database:

The machine is to pick from the multiple choices (a) sweater (b) yacht (c) arm (d) rail. Again, I doubt that any person, of sufficient age, would be confused by this example and so wonder why. We are literally surrounded with ambiguous expressions every day. Casual speech thrives on these corner-cutting measures. Even our formal writings are not immune; there are numerous examples of these types of anaphoras in all sorts of literature with the epistles of St. Paul ranking up there for complexity and frequency. Humans manage quite nicely to deal with them – a tribute to the innate intelligence of the species as a whole.

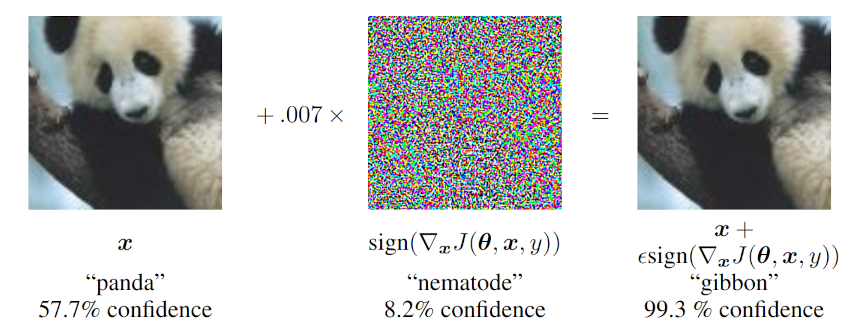

But knowing humans to be intelligent and observing them being able to deal with these types of ambiguity does not mean the converse if true. Being able to pass the WSC does not mean the agent is necessarily smart. The argument for this conclusion comes, disappointingly, from the fact that it has already been overcome by various algorithms 7 years after its proposal. Sampling the associated papers, the reader will soon find that much of the magic comes from a different flavor of statistical association, indicating that the real intellect resides in the algorithm designer. This is a point raised by The Defeat of the Winograd Schema Challenge by Vid Kocijan, Ernest Davis, Thomas Lukasiewicz, Gary Marcus, Leora Morgenstern. To quote from section 4 of their paper:

The Winograd Schema Challenge as originally formulated has largely been overcome. However, this accomplishment may in part reflect flaws in its formulation and execution. Indeed, Elazar et al. (2021) argue that the success of existing models at solving WSC may be largely artifactual. They write:

We provide three explanations for the perceived progress on the WS task: (1) lax evaluation criteria, (2) artifacts in the datasets that remain despite efforts to remove them, and (3) knowledge and reasoning leakage from large training data.

In their experiments, they determined that, when the form of the task, the training regime, the training set, and the evaluation measure were modified to correct for these, the performance of existing language models dropped significantly.

At the end of the day, I think it is still safe to say that researchers are clever in finding ways to mimic intelligence in small slices of experience but that nothing still approaches the versatility and adaptability of the human mind.