Multivariate Gaussian – Part 2

This month’s blog continues the exploration begun in the last installment, which covered how to evaluate and normalize multivariate Gaussian distributions. The focus here will be on evaluating moments of these distributions. As a reminder, the prototype example is from Section 1.2 of Brezin’s text Introduction to Statistical Field Theory, where he posed the following toy problem for the reader:

\[ E[x^4 y^2] = \frac{1}{N} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x^4 y^2 e^{-(x^2 + xy + 2 y^2)} \; , \]

where the normalization constant $N$, the value of the integral with only the exponential term kept, is found, as described in the last post, by re-expressing the exponent of the integrand as a quadratic form $r^T A r/2$ (where $r$ presents the independent variables as a column array) and then expressing the value of the integral in terms of the determinant of the matrix $A$: $N = (2 \pi)^{(n/2)}/\sqrt{\det{A}}$. Note: for reasons that will become apparent below, the scaling of the quadratic form was changed with the introduction of a one-half in the exponent. Under this scaling $A \rightarrow A/2$ and $\det{A} \rightarrow \det{A}/2^n$, where $n$ is the dimensionality of the space.

To evaluate the moments, we first extend the exponent by ‘coupling’ it to an $n$-dimensional ‘source’ $b$ via the introduction of the term $b^T r$ in the exponent. The integrand becomes:

\[ e^{-r^T A r/2 + b^T r} . \]

The strategy for manipulating this term into one we can deal with is akin to usual ‘complete the square’ approach in one dimension but generalized. We start by defining a new variable

\[ s = r \, – A^{-1} b \; .\]

Regardless of what $b$ is (real positive, real negative, complex, etc.) the original limits on the $r_i \in (-\infty,\infty)$ carry over to $s$. Likewise, the measures of the two variables are related by $d^ns =d^nr$. In terms of the integral, this definition simply moves the origin of the $s$ relative to the $r$ by an amount $A^{-1}b$, which results in no change since the range is infinite.

Let’s manipulate the first term in the exponent step-by-step. Expanding the right side gives

\[ r^T A (s + A^{-1} b) = r^T A s + r^T b \; .\]

Since $A$ is symmetric, its inverse is too, $\left( A^{-1} \right)^T = A^{-1}$ and this observation allows us to now expand the first term side, giving

\[ (s^T + b^T A^{-1} ) A s + r^T b = s^T A s + b^T s + r^T b \; . \]

Next note that $b^T r = b_i r_i = r^T b$ (summation implied) and then substitute these pieces into the original expression to get

\[ -r^T A r/2 – b^T r = -( s^T A s + b^T s + b^T r)/2 + b^T r \\ = -s^T A s + b^T ( r – s )/2 \; . \]

Finally, using the definition of $s$ the last term can be simplified to eliminate both $r$ and $s$, leaving

\[ -r^T A r = -s^T A s + b^T A^{-1} b /2 \; .\]

The original integral $I = \int d^n r \exp{(-r^T A r/2 + b^T r)}$ now becomes

\[ I = e^{-b^T A^{-1} b/2} \int d^n s \, e^{-s^T A s} = e^{-b^T A^{-1} b/2} \, \frac{(2 \pi)^{(n/2)}}{\sqrt{\det{A}}} \; . \]

This result provides us with the mechanism to evaluate any multivariate moment of the distribution by differentiating with respect to $b$ and then setting $b=0$ afterwards.

For instance, if $r^T = [x,y]$, then the moment of $x$ with respect to the original distribution of the Brezin problem is

\[ E[x] = \frac{1}{N} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x e^{-(x^2 + xy + 2 y^2)} \; , \]

where $N = 2\pi/\sqrt{\det{A}}$.

Our expectation is, by symmetry, that this integral is zero. We can confirm that by noting that first that the expectation value is given by

\[ E[x;b] = \frac{\partial}{\partial b_x } \frac{1}{N} \int dx \, dy \, e^{-r^T A r + b_x x + b_y y} \\ = \frac{1}{N} \int dx \, dy \, x e^{-r^T A r + b_x x + b_y y} \; ,\]

where the notation $E[x;b]$ is adopted to remind us that we have yet to set $b=0$.

Substituting the result from above gives

\[ E[x] = \left. \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial b_x } e^{b^T A^{-1} b/2} \right) \right|_{b=0} \\ = \left. \frac{\partial}{\partial b_x} (b^T A^{-1} b)/2 \right|_{b=0} \; , \]

where, in the last step, we used $\left. e^{b^T A^{-1} b} \right|_{b=0} = 1$.

At this point it is easier to switch to index notation when evaluating the derivative to get

\[ E[x] = \left. \frac{\partial}{\partial b_x} (b_i (A^{-1})_{ij} b_j/2) \right|_{b=0} = \left. (A^{-1})_{xj} b_j \right|_{b=0} = 0 \; ,\]

where rationale for the scaling by $1/2$ now becomes obvious.

At this point, we are ready to tackle the original problem. For now, we will use a symbolic algebra system to calculate the required derivatives, deferring until the next post some of the techniques needed to simplify and generalize these steps. In addition, for notational simplicity, we assign $B = A^{-1}$.

Brezin’s problem requires that

\[ A = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 4 \end{array} \right] \; \]

and that

\[ B = A^{-1} = \frac{1}{7} \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 4 & -1 \\ -1 & 2 \end{array} \right] \; .\]

The required moment is related to the derivatives of $b^T B b$ as

\[ E[x^4y^2] = \left. \frac{\partial^6}{\partial b_x^4 \partial b_y^2 } e^{b^T B b/2} \right|_{b=0} = 3 B_{xx}^2 B_{yy} + 12 B_{xx} B_{xy}^2 \; . \]

Substituting from above yields

\[ E[x^4 y^2] = 3 \left( \frac{4}{7} \right)^2 \frac{2}{7} + 12 \frac{4}{7} \left( \frac{-1}{7} \right)^2 \; , \]

which evaluates to

\[ E[x^4 y^2] = \frac{96}{343} + \frac{48}{343} = \frac{144}{343} \; . \]

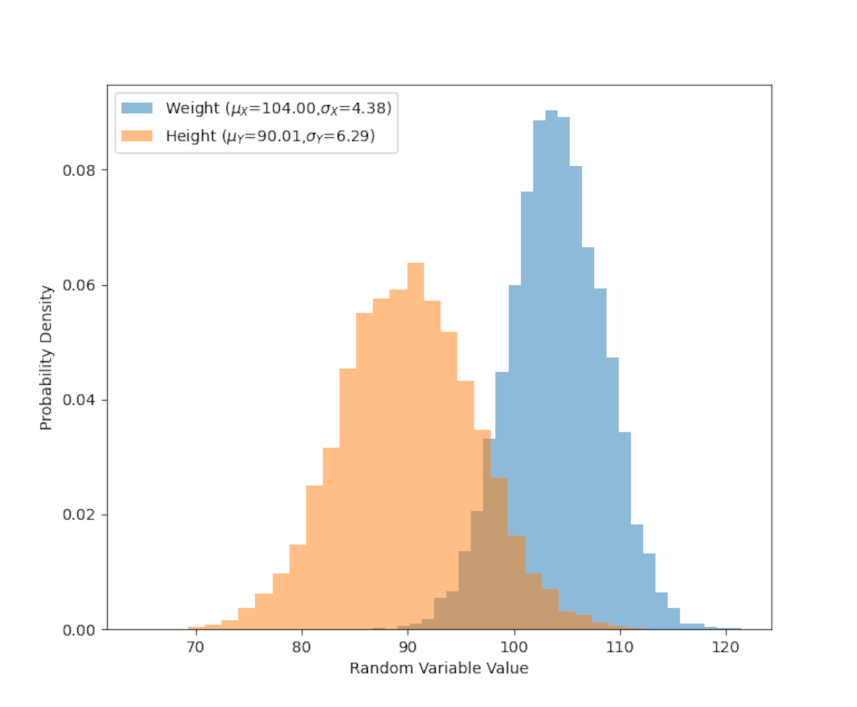

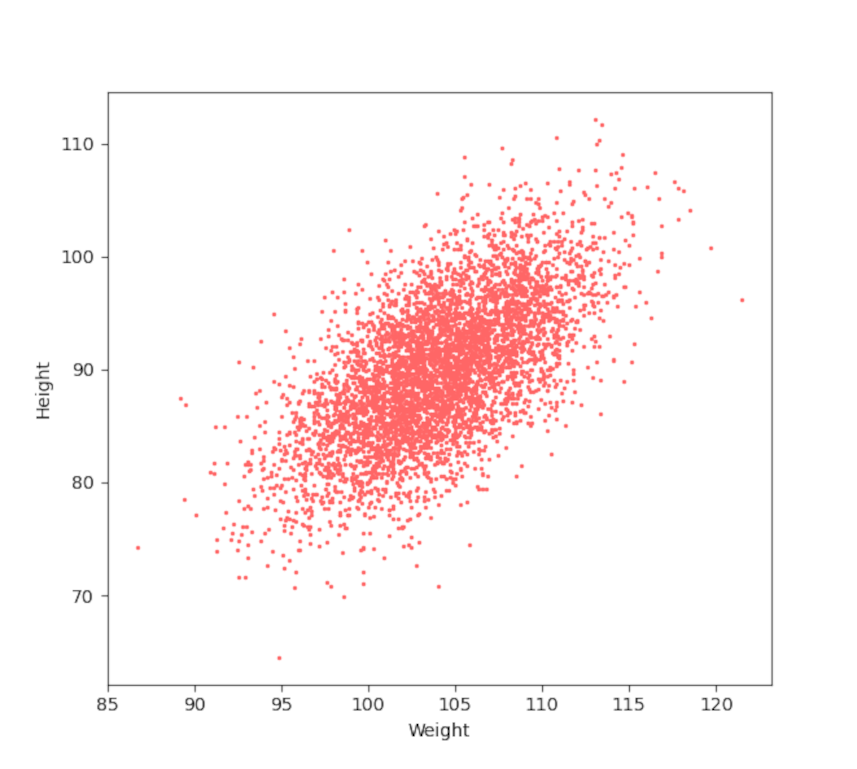

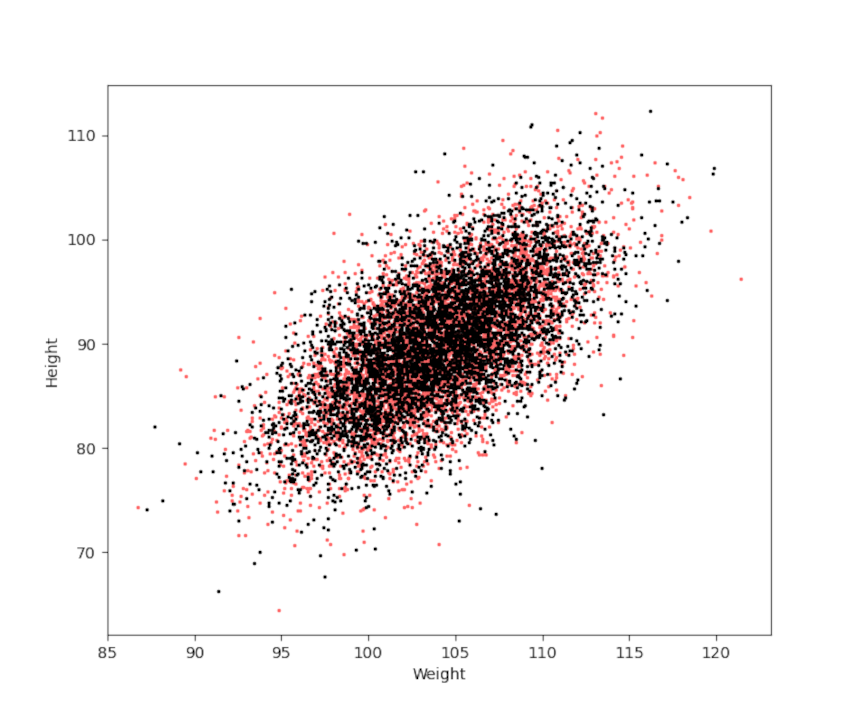

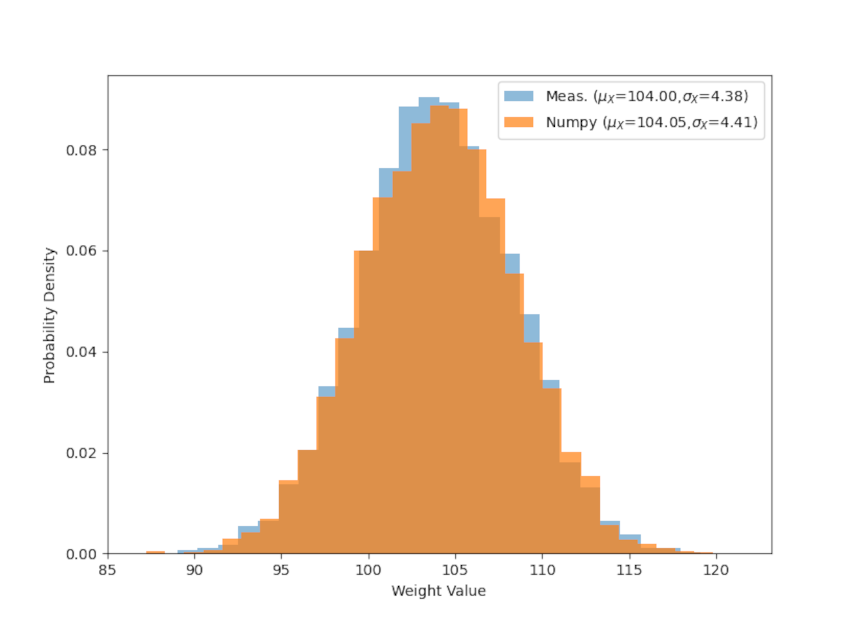

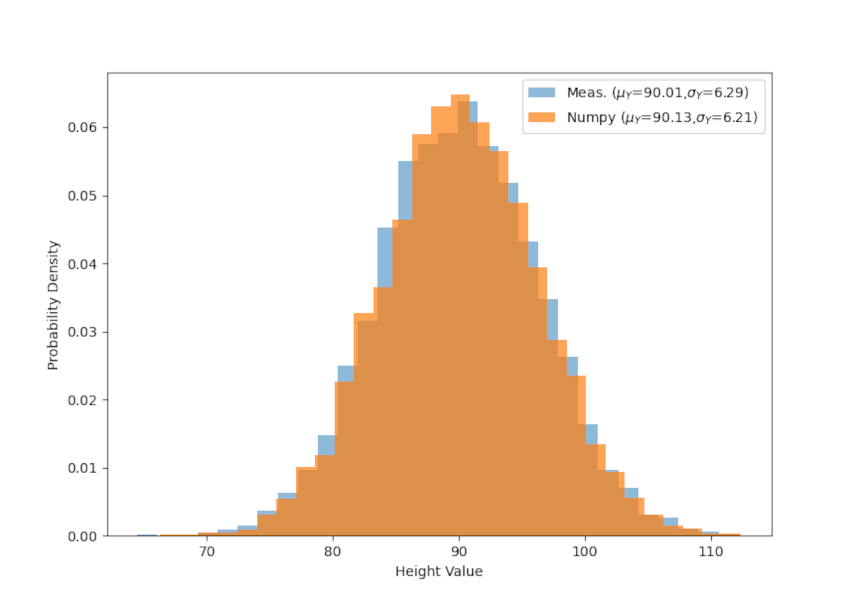

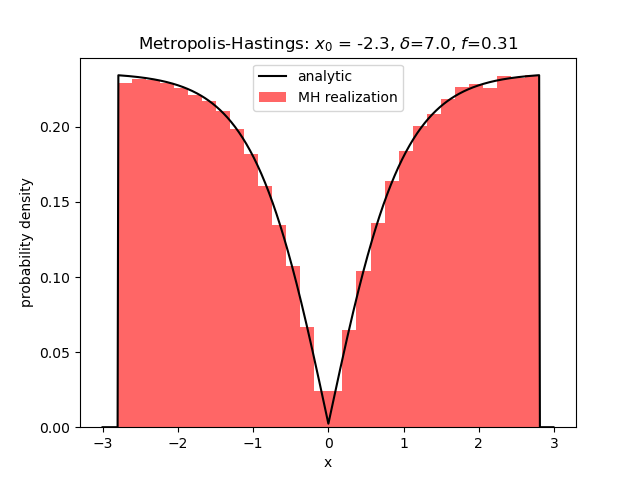

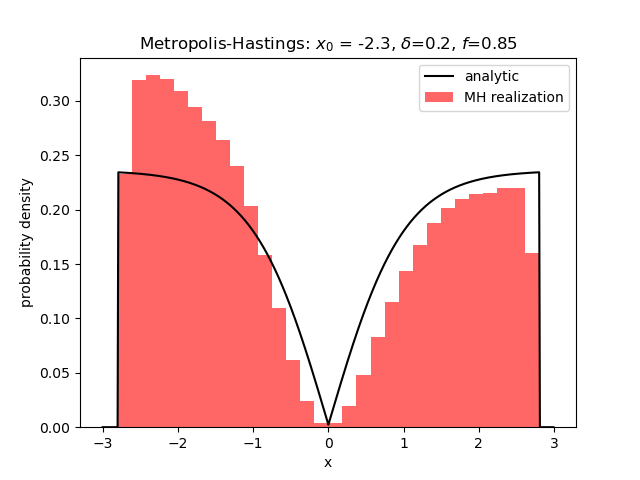

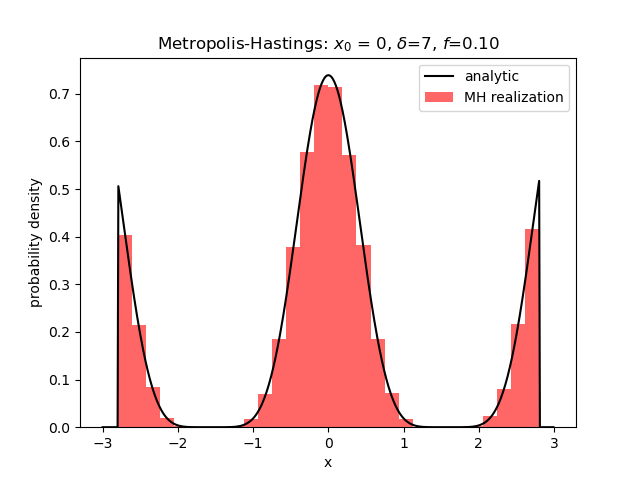

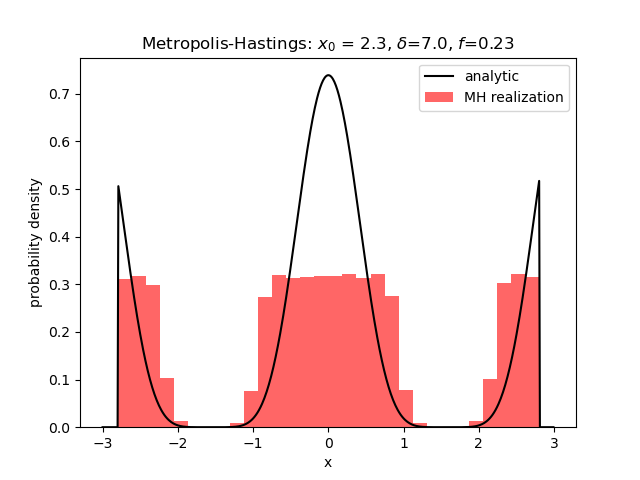

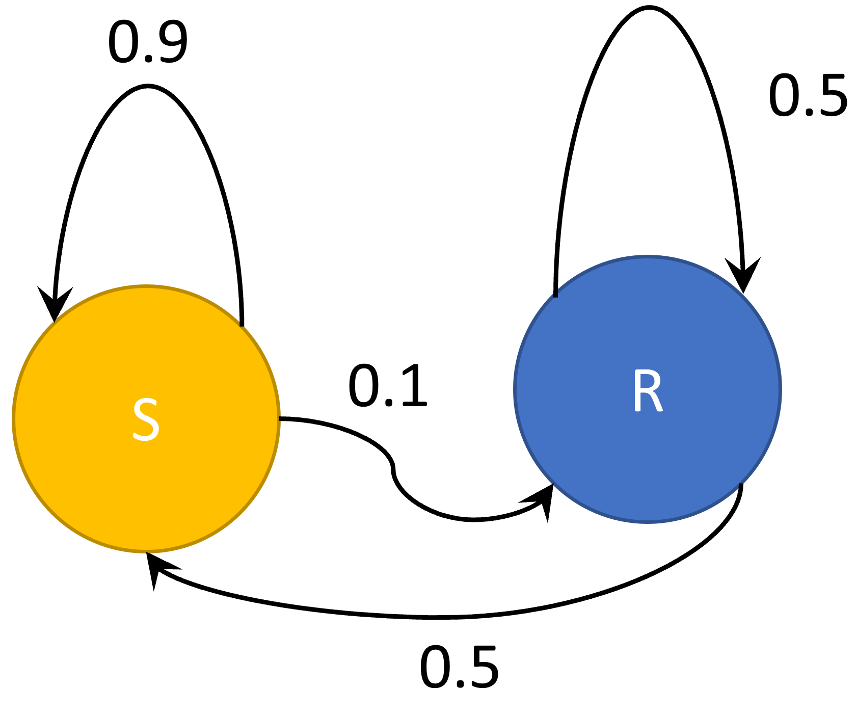

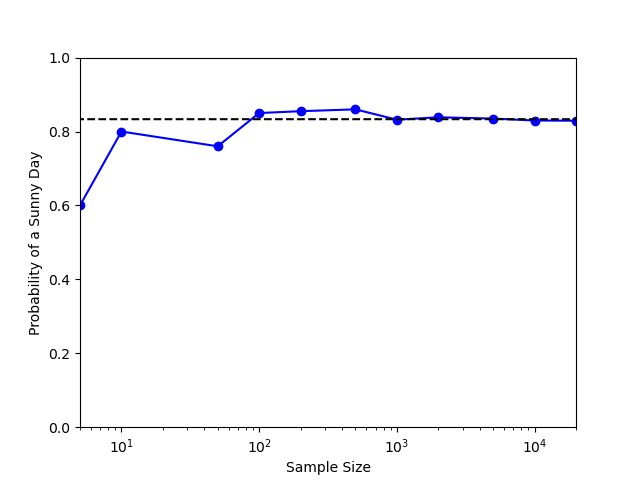

A brute force Monte Carlo evaluation gives the estimate $E[x^4 y^2] = 0.4208196$ compared with the exact decimal representation of $0.4198251$, a $0.24\%$ error, which is in excellent agreement.