In last week’s article, I discussed some of the interesting contributions to the scientific method made by the pair of English Bacons, Roger and Francis. A common and central theme to both of their approaches is the emphasis they placed on performing experiments and then inferring from those experiments what the logical underpinning was. Put another way, both of these philosophers advocated inductive reasoning as a powerful tool for understanding nature.

One of the problems with the inductive approach is that in generalizing from a few observations to a proposed universal law one may overreach. It is true that, in the physical sciences, great generalizations have been made (e.g., Newton’s universal law of gravity or the conservation of energy) but these have ultimately rested on some well-supported philosophical principles.

For example, the conservation of momentum rests on a fundamental principle that is hard to refute in any reasonable way; that space has no preferred origin. This is a point that we would be loath to give up because it would imply that there was some special place in the universe. But since all places are connected (otherwise they can’t be places) how would nature know to make one of them the preferred spot and how would it keep such a spot inviolate?

But in other matters, where no appeal can be made to an over-arching principle as a guide, the inductive approach can be quite problematic. The classic and often used example of the black swan is a case in point. Usually the best that can be done in these cases is to make a probabilistic generalization. We infer that such and such is the most likely explanation but by no means necessarily the correct one.

The probabilistic approach is time honored. William of Occam’s dictum that the simplest explanation that fits all the available facts is usually the correct one is, at its heart, a statement about probabilities. Furthermore, general laws of nature started out as merely suppositions until enough evidence and corresponding development of theory and concepts led to the principles upon which our confidence rests.

So the only thorny questions are what are meant by ‘fact’ and ‘simplest’. On these points, opinions vary and much argument ensues. In this post, I’ll be exploring one of the more favored approaches for inductive inference known as the Bayesian method.

The entire method is based on the theorem attributed to Thomas Bayes, a Presbyterian minister, and statistician, who first published this law in the latter half of the 1700s. It was later refined by Pierre Simon Laplace, in 1812.

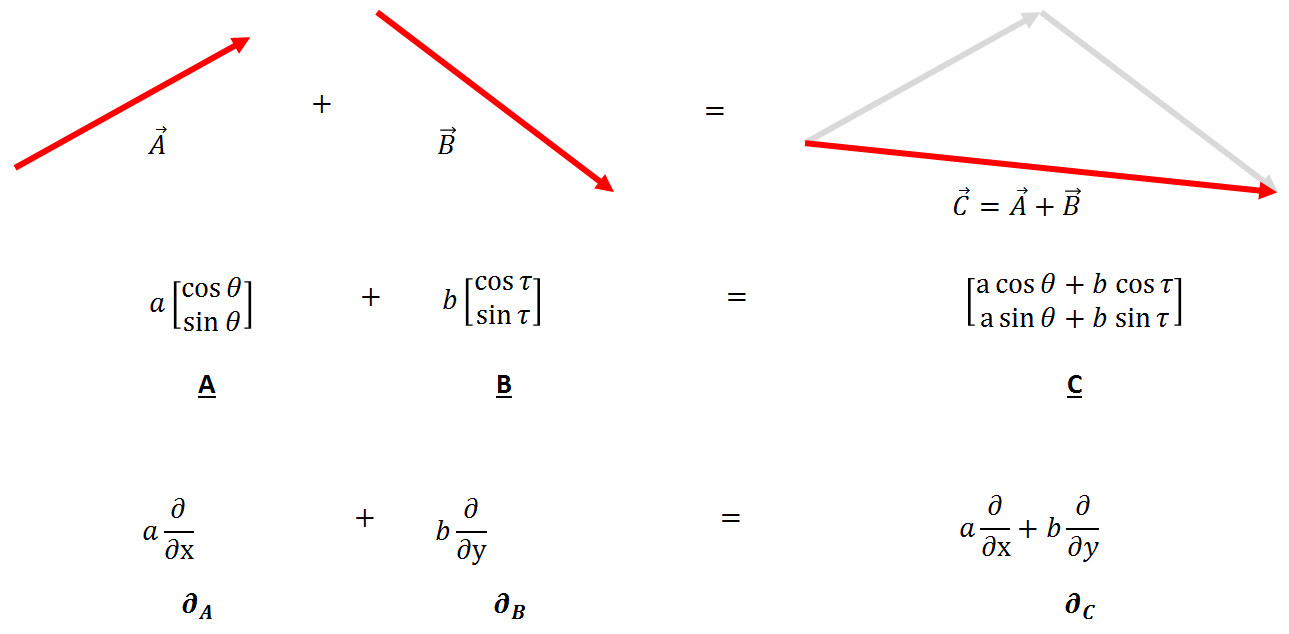

The theorem is very easy to write down, and that perhaps is what hides its power and charm. We start by assuming that two random events, $A$ and $B$, can occur, each according to some probability distribution. The random events can be anything at all and don’t have to be causally connected or correlated. Each event has some possible set of outcomes $a_1, a_2, \ldots$ and $b_1, b_2, \ldots$. Mathematically, the theorem is written as

\[ P(a_i|b_j) = \frac{P(b_j|a_i) P(a_i)}{P(b_j)} \; , \]

where $a_i$ and $b_j$ are some specific outcomes of the events $A$ and $B$ and $P(a_i|b_j)$ ($P(b_j|a_i)$) is called the conditional probability that $a_i$ ($b_j$) results given that we know that $b_j$ ($a_i$) happened. As advertised it is nice and simple to write down and yet amazingly rich and complex in its applications. To understand the theorem, let’s consider a practical case where the events $A$ and $B$ take on some easy-to-understand meaning.

Suppose that we are getting ready for Christmas and want to decorate our tree with the classic strings of different-colored lights. We decide to a purchase a big box of bulbs of assorted colors from the Christmas light manufacturer, Brighty-Lite, who provides bulbs in red, blue, green, and yellow. Allow the set $A$ to represent the colors

\[ A = \left\{\text{red}, \text{blue}, \text{green}, \text{yellow} \right\} = \left\{r,b,g,y\right\} \; . \]

On its website, Brighty-Lite proudly tells us that they have tweaked their color distribution in the variety pack to best match their customer’s desires. They list their distribution as consisting of 30% percent red and blue, 25% green, and 15% yellow. So the probabilities associated with reaching into the box and pulling out a bulb of a particular color are

\[ P(A) = \left\{ P(r), P(b), P(g), P(y) \right\} = \left\{0.30, 0.30, 0.25, 0.15 \right\} \; . \]

The price for bulbs from Brighty-Lite is very attractive, but being cautious people, we are curious how long the bulbs will last before burning out. We find a local university that put its undergraduates to good use testing the lifetimes of these bulbs. For ease of use, they categorized their results into three bins: short, medium, and long lifetimes. Allowing the set $B$ to represent the lifetimes

\[ B = \left\{\text{short}, \text{medium}, \text{long} \right\} = \left\{s,m,l\right\} \]

the student results are reported as

\[ P(B) = \left\{ P(s), P(m), P(l) \right\} = \left\{0.40, 0.35, 0.25 \right\} \; , \]

which confirmed our suspicions that Brighty-Lite doesn’t make its bulbs to last. However, since we don’t plan on having the lights on all the time, we decide to buy a box.

After receiving the box and buying the tree, we set aside a weekend for decorating. Come Friday night we start by putting up the lights and, as we work, we start wondering whether all colors have the same lifetime distribution or whether some colors are more prone to be short-lived compared with the others. The probability distribution that describes the color of the bulb and its lifetime is known as the joint probability distribution.

If the bulb color doesn’t have any effect on the lifetime of the filament, then the events are independent, and the joint probability of, say, a red bulb with a medium lifetime is given by the product of the probability that the bulb is red and the probability that it has a medium lifespan (symbolically $P(r,m) = P(r) P(m)$).

The entire full joint probability distribution is thus

| |

red |

blue |

green |

yellow |

|

| short |

0.12 |

0.12 |

0.1 |

0.06 |

0.40 |

| medium |

0.105 |

0.105 |

0.0875 |

0.0525 |

0.35 |

| long |

0.075 |

0.075 |

0.0625 |

0.0375 |

0.25 |

| |

0.30 |

0.30 |

0.25 |

0.15 |

|

Now we are in a position to see Bayes theorem in action. Suppose that we pull out a green bulb from the box. The conditional probability that the lifetime is short $P(s|g)$ is the relative proportion that the green and short entry $P(g,s)$ has compared to the sum of the probabilities $P(g)$ found in the column labeled green. Numerically,

\[ P(s|g) = \frac{P(g,s)}{P(g)} = \frac{0.1}{0.25} = 0.4 \; . \]

Another way to write this is as

\[ P(s|g) = \frac{P(g,s)}{P(g,s) + P(g,m) + P(g,l)} \; , \]

which better shows that the conditional probability is the relative proportion within the column headed by the label green.

Likewise, the conditional probability that the bulb is green given that its lifetime is short is

\[ P(g|s) = \frac{ P(g,s) }{P(r,s) + P(b,s) + P(g,s) + P(y,s)} \; . \]

Notice that this time the relative proportion is measured against joint probabilities across the colors (i.e., across the row labeled short). Numerically, $P(g|s) = 0.1/0.4 = 0.25$.

Bayes theorem links these two probabilities through

\[ P(s|g) = \frac{ P(g|s) P(s) }{ P(g) } = \frac{0.25 \cdot 0.4}{0.25} = 0.4 \; , \]

which is happily the value we got from working directly with the joint probabilities.

The next day, we did some more cyber-digging and found that a group of graduate students at the same university extended the undergraduate results (were they perhaps the same people?) and reported the following joint probability distribution:

| |

red |

blue |

green |

yellow |

|

| short |

0.15 |

0.10 |

0.05 |

0.10 |

0.40 |

| medium |

0.05 |

0.12 |

0.15 |

0.03 |

0.35 |

| long |

0.10 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.25 |

| |

0.30 |

0.30 |

0.25 |

0.15 |

|

Sadly, we noticed that our assumption of independence between the lifetime and color was not borne out by experiment since $P(A,B) \neq P(A) \cdot P(B)$ or in more explicit terms $P(color,lifetime) \neq P(color) P(lifetime)$. However, we were not completely disheartened since Bayes theorem relates relative proportions and, therefore, it might still work.

Trying it out, we computed

\[ P(s|g) = \frac{P(g,s)}{P(g,s) + P(g,m) + P(g,l)} = \frac{0.05}{0.05 + 0.15 + 0.05} = 0.2 \]

and

\[ P(g|s) = \frac{ P(g,s) }{P(r,s) + P(b,s) + P(g,s) + P(y,s)} \\ = \frac{0.05}{0.15 + 0.10 + 0.05 + 0.10} = 0.125 \; . \]

Checking Bayes theorem, we found

\[ P(s|g) = \frac{ P(g|s) P(s) }{ P(g) } = \frac{0.125 \cdot 0.4}{0.25} = 0.2 \]

guaranteeing a happy and merry Christmas for all.

Next time, I’ll show how this innocent looking computation can be put to subtle use in inferring cause and effect.