A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the subtle difficulties surrounding the mathematics and programming of vectors. The representation of a generic vector by a column array made the situation particularly confusing, as one type of vector was being used to represent another type. The central idea in that post was that the representation of an object can be very seductive; it can cloud how you think about the object, or use it, or program it.

Well, this idea about representations has, itself, proven to be seductive, and has lead me to think about the human capacity that allows imagination to imbue representations of things with a life of their own.

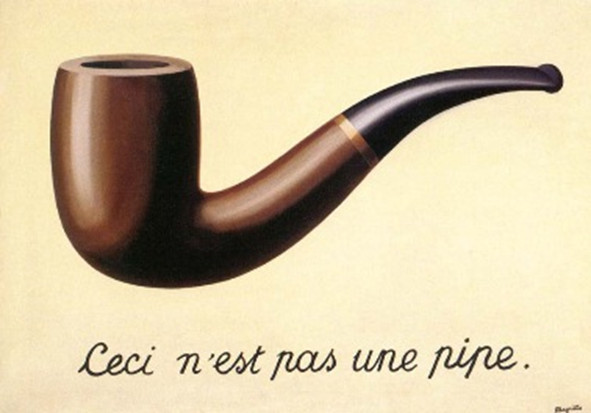

To set the stage for this exploration, consider the well-known painting entitled The Treachery of Images by the French painter Magritte.

The translation of the text in French at the bottom of the painting reads “This is not a pipe.” Magritte’s point is that the image of the pipe is a representation of the idea of a pipe but is not a pipe itself; hence his choice of the word ‘treachery’ in the title of his painting.

Of course, this is exactly the point I was making in my earlier post, but a complication in my thinking arose that sheds a great deal of light on the human condition and has implications for true machine sentience.

I was reading Scott McCloud’s book Understanding Comics, when he presented a section on what makes sequential art so compelling. In that section, McCloud talks about the inherent mystery that allows a human, virtually any human old enough to read, to imagine many things while reading a comic. Some of the things that the reader imagines include:

- Action takes place in the gutters between the panels

- Written dialog is actually being spoken

- That strokes of pencil and pen and color are actually things.

You, dear reader, are also engaging in this kind of imagining. The words you are reading – words that I once typed – are not even pen and pencil strokes on a page. The whole concept of page and stroke is, of course, virtual: tracings of different flows of current and voltage humming through micro-circuitry in your computer.

Not only is that painting of Magritte’s shown above not a pipe, it’s not a painting. It is simply a play of electronic signals on a computer monitor and a physiological response in the eye. And yet, how is it that it is so compelling?

What is the innate capacity of the human mind and the human soul to be moved by arrangements of ink on a page, by the juxtaposition of glyphs next to each other, by movement of light and color on a movie screen, by the modulated frequencies that come out of speakers and headphones? In other words, what is the human capacity that breathes life into the signs and signals that surrounds us?

Surely someone will rejoin “it’s a by-product of evolution” or “it’s just the way we are made”. But these types of responses, as reasonable as they may be, do nothing to address the root faculty of imagination. They do nothing to address the creativity and the connectivity of the human mind.

As a whimsical example, consider this take on Magritte’s famous painting, inspired by the world of videogames.

Humans have that amazing ability to connect to different ideas by some tenuous association to find a marvelous (or at least funny) new thing. The connections that lead from the ‘pipe’ you smoke to the virtual ‘pipe’ in Mario Brothers are obvious to anyone who has been exposed to both of them in context. And yet, how do you explain them to someone who hasn’t? Even more interesting: how do you enable a machine to make the same connection, to find the imagery funny? In short, how can we come to understand imagination and, perhaps, imitate it?

Maybe we really don’t want machines that actually emulate human creativity, but we won’t know or understand the limitations of machine intelligence without more fully exploring our own. And surely one vital component of human intelligence is the ability to flow through the treachery of images into the power of imagination.