A Symbolic Experiment – Part 1: First Expression

One of the most active areas of artificial intelligence in the earlier days (say from 1960s through the 1990s) was the development of symbolic AI to handle mathematical manipulations. In his book, Paradigms of Artificial Intelligence Programming: Case Studies in Common Lisp, Peter Norvig covers numerous applications that were solved as the ‘hot’ topics of the day; a time before the before the advent of deep learning came along and convinced most people that LLM’s and agentic systems would solve all the world’s problems. However, these former hot topics are still relevant today and I thought that it might be interesting to explore a bit to see what can be done with ‘old fashioned’ symbolic manipulation.

There are three reasons for embarking on this exploration.

First, understanding the nuts and bolts of symbolic manipulation makes one a better user of the ‘professional’ computer algebra systems (CASs) on the market today, such as wxMaxima, Maple, Mathematica, and SymPy. Each of these is polished and abstracted (to varying degrees) and seeks to help the user, typically a mathematician, scientist, or engineer, in making a model and subsequently applying it to some specific problem. However, each of these systems (especially the for-profit ones), want the user to be able to solve problems immediately without, necessarily, knowing how the CAS works behind the scenes. While these systems are quite powerful (again to lesser or greater degrees), experience has shown that most users don’t/can’t take full advantage of the system unless they can program in it. And to program in it requires a firm understanding of at least the rudiments of what is happening under the hood. This is a sentiment Norvig emphases repeatedly in his book, most notably by providing the following quote:

You think you know when you learn, are more sure when you can write, even more when you can teach, but certain when you can program.

–Alan Perlis, Yale University computer scientist

Second, there are always new mathematics being invented with brand new rules. Being able to manipulate/simplify and then mine an expression for meaning transcends blindly applying a built-in trig rule like $\cos^2 + \sin^2 = 1$, a generic ‘simplify’ method, or some such thing. It often requires understanding how an expression is formed and what techniques can be used to take an expression apart and reassemble as something more useful.

Third, and finally, it’s fun – plain and simple – and most likely will be a gateway activity for even more fun to come.

Not that we’ve resolved to explore, the next choice is which part of terra incognita. The undiscovered country that I’ve chosen is the implementation of a simple set of symbolic rules, via pattern matching, that implement some of the basic properties of the Fourier Transform.

For this first experiment, I chose Sympy as the tool of choice as it seemed a natural one since it provides the basic machinery of symbolic manipulation for free in Python but it doesn’t have a particularly sophisticated set of rules associated with the Fourier Transform. For example, SymPy version 1.14 knows that the transform is linear but it doesn’t know how to simplify the Fourier Transform based on the well-known rule:

\[ {\mathcal F}\left[ \frac{\partial f(t)}{\partial t} \right] = i \omega {\mathcal F}\left[ f(t) \right] \; , \]

which is one of the most important relationships for the Fourier Transform as it allows us to convert differential equations into algebraic ones, which is one of the primary motivations for employing it (or any other integral transform for that matter).

Before beginning, let’s set some notation. Functions in the time domain will be denoted by lower case Latin letters (e.g., $f$, $g$, etc.) and will depend on the variable $t$. The corresponding Fourier Transform will be denoted by upper case Latin letters (e.g., $F$, $G$, etc.) and will depend on the variable $\omega$. Arbitrary constants will also be denoted by lower case Latin letters but usually from the beginning of the alphabet (e.g., $a$, $b$, etc.). The pairing between the two will be symbolically written as:

\[ F(\omega) = {\mathcal F}(f(t)) \; ,\]

with an analogous expression for the inverse. The sign convention will be chosen so that the relationship for the transform of the derivative is as given above.

For the first experiment, I chose the following four rules/properties of the Fourier Transform:

- Linearity: ${\mathcal F}(a \cdot f(t) + b \cdot g(t) ) = a F(\omega) + b G(\omega)$

- Differentiation: $\mathcal{F}\left[\frac{d^n f(t)}{dt^n}\right] = (i \omega)^n F(\omega)$

- Time Shifting: $\mathcal{F}{f(t – t_0)} = e^{-i \omega t_0} F(\omega)$

- Frequency Shifting: $\mathcal{F}{e^{i \omega_0 t} f(t)} = F(\omega – \omega_0)$

We expect freshman or, at worst, sophomores in college to absorb and apply the rules above and, so, we may be inclined to think that they are ‘straightforward’ or ‘boring’ or ‘dull’. But, finding a way to make a computer do algorithmically what we expect teenagers to pick up from a brief lecture and context is surprisingly involved.

Our hypothetical college student’s capacity to learn, even when not explicitly taught is an amazing and often overlooked miracle of the human animal. Unfortunately, teaching any computer to parse ‘glyphs on a page’ in a way that mimics what a person does requires a lot of introspection into just how the symbols are being interpreted. Mathematical expressions are slightly easier as they tend to have less ‘analogical elasticity’; that is to say, that by their very nature, mathematical terms and symbols tend to be more rigid that everyday speech. More rigid doesn’t mean completely free of ambiguities as the reader may reflect on when thinking about what the derivatives in the Euler-Lagrange equations actually mean:

\[ \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial {\dot q}} \right) – \frac{\partial L}{\partial q} = 0 \; . \]

Let’s start with a simple mathematical expression that is needed for the Linearity property

\[ a \cdot f(t) + b \cdot g(t) \; . \]

When composing this expression, a person dips into the standard glyphs of the English alphabet (10 of them to be precise) and simply writes them down. If pressed, the person may go onto say “where $a$ and $b$ are constants and $f$ and $g$ are, as yet undefined functions of the time variable $t$”. But the glyphs on the page remain all the same. For a computer, are the glyphs ‘a’ and ‘b’ of the same type as the glyphs ‘f’ and ‘g’? And where does ‘(t)’ figure in?

SymPy’s answer to this (which matches most of the other CASs) is that ‘a’, ‘b’, and ‘t’ are Symbols and ‘f’ and ‘g’ are undefined Functions. The bold-face terms are syntactically how SymPy creates these symbolic objects. These objects can be used as ordinary Python objects with all the normal Python syntax (e.g., print(), len(), type(), etc.) coming along because SymPy tries to strictly adhere to the Python data model. As a result, we can form new expressions by using ‘+’ and ‘*’ without worrying about how SymPy chooses to add and multiply it various objects together.

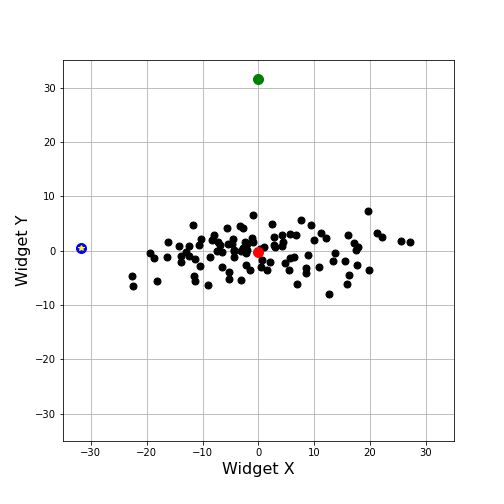

The following figure shows the output of a Jupyter notebook that implements these simple steps.

As expected, querying type(a) gives back sympy.core.symbol.Symbol and type(f) returns sympy.core.function.UndefinedFunction. And, as expected, we can form our first expression

from using ‘+’ and ‘*’ as effortlessly as we wrote the analogous expression above out of basic glyphs, without having to worry about details. But what to make of type(my_expr) returning sympy.core.add.Add?

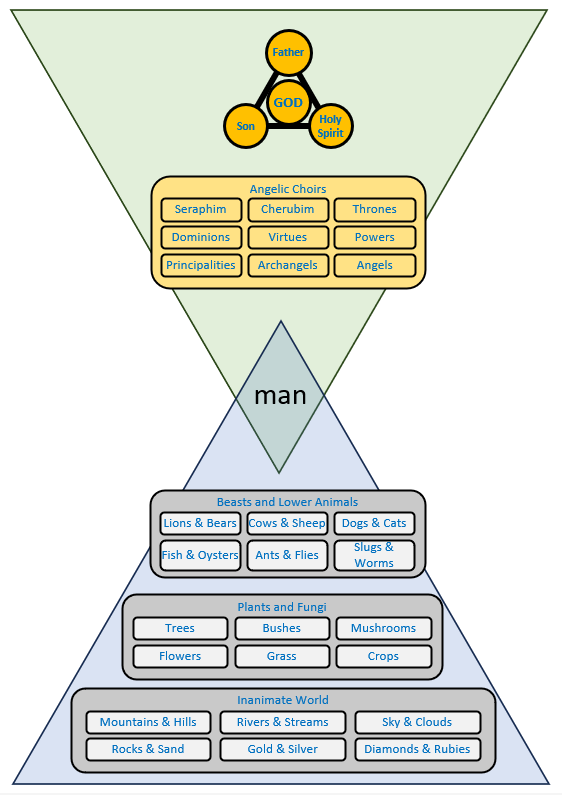

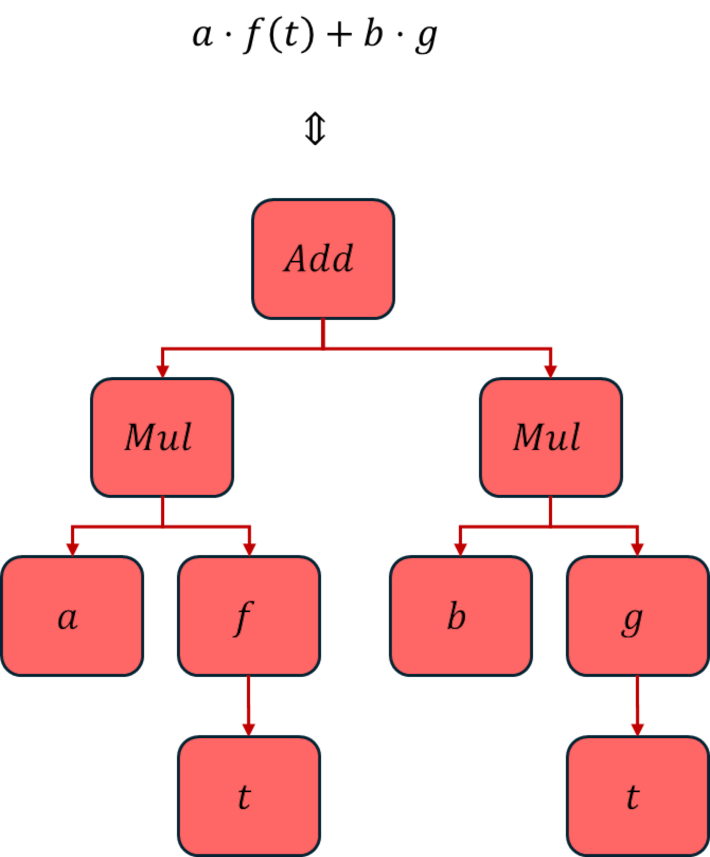

The answer to this question gets at the heart of how most (if not all) CASs work. What we humans take for granted as a simple expression $a \cdot f(t) + b \cdot g(t)$ is, for SymPy (and all the other CASs that I’ve seen), a tree. The top node is this case is Add meaning that ‘+’ is the root and each of the two subexpressions ($a \cdot f(t)$ and $b \cdot g(t)$) are child nodes, each of type sympy.core.mul.Mul. SymPy symbols are atomic nodes that can only be root nodes or child nodes but can never serve as parent nodes. And the distinction between the Symbol and Function objects are now much clearer: giving a glyph the designation as a Function means it can serve as a parent node, even if all of its behavior is, as yet, undefined.

The innocent-looking expression from above has the tree-form

Next month, we’ll continue on to show how to examine, traverse, and modify this tree structure so that we can mimic how a human ‘plays with’ and ‘mine meaning from’ an expression.