Recently I started re-reading Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose. The action is set in the early part of the 14th century (November of 1327 to be precise) at a Benedictine abbey whose name, to quote the fictitious narrator, “it is only right and pious now to omit.” One of the many themes of this novel, reflecting the scholastic philosophy ascendant at that time, deals with the nature of being human. Answering that ontological/anthropological question includes, as correlative concepts, the licitness of laughter and a categorization of the essential nature of what separates us from the lower animals, which philosophers often will call the beasts.

While being removed from our time by approximately 800 intervening years, the basic question as to ‘what is man’ is still as operative today as it was then or as it ever was. The yardsticks have changed but the question remains.

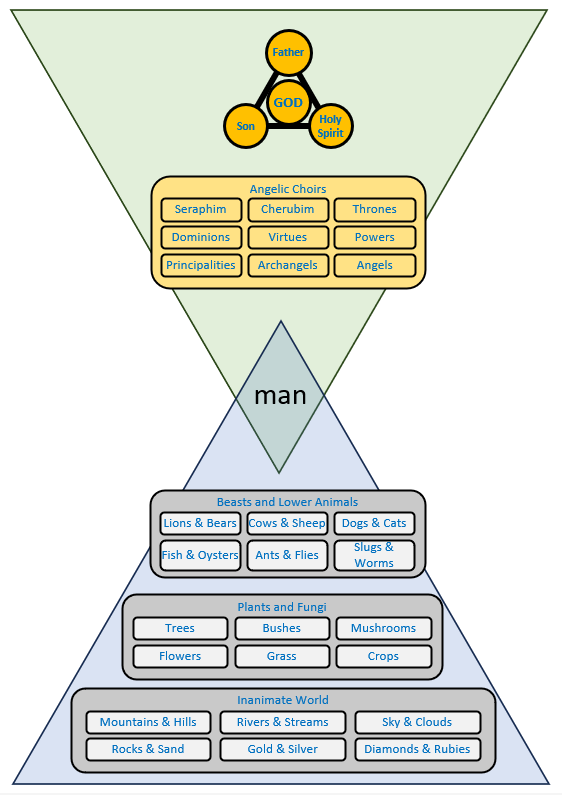

The aforementioned Scholastics crafted an image of the universe similar to what is shown below.

The universe consists of an abundant material world (contained in the blue triangle) with a hierarchy of complexity that I think a modern biologist would agree with (after he, of course, added all the still controversial divisions associated with microscopic life). At the lowest rung is the inanimate matter that makes bulk of the world around us in the form of solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. The next rung up (again skipping microscopic life, which, while important, was unknown prior to the late 1600s) consists of what was often called the vegetable kingdom comprised of the plants and plant-like life around us. Animals of all sorts, excepting man (philosophers typically call this subset ‘the beasts’ for brevity), comprise the next level up. The pinnacle of this material world is occupied by humans, a point that, although some among us would wish it not to be true, is difficult to refute.

The universe also consists of an abundant spiritual world (contained in the green triangle) with a hierarchy of complexity that is far more controversial because it elusively remains beyond our physical means of detection. For a Christian philosopher in the Middle Ages, the top of the hierarchy is the triune God composed of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as 3 persons in one being. Below the Trinity, the Scholastics imagined a world teaming with angels, the composition of which is traditionally divided into three choirs each comprised of three species according to the analysis of Thomas Aquinas. Finally, the lowest level of the spiritual realm is occupied by human beings.

Thus, a scholastic philosopher recognizes that the nature of man is a unique union between material and the spiritual, but the measure of man – what exactly separates him at that intersection from the more numerous species belonging entirely to either world – isn’t so clear.

One might think that as Western thought transitioned from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance and eventually through the Enlightenment and into our current Industrial/Digital age that the question would lose all of its force, but it stubbornly remains; only the trappings have changed. Where once an operative question was ‘how many angels could dance on a pinhead’ (and rightly so) we now ask questions about how many of those spiritual beings we label as ‘AI’ are needed to replace a screenwriter or a lawyer.

So, let’s examine some of the various activities that have been put forth as ways that Man separates himself both the beasts and, where appropriate, from the AI.

For our first activity, there is Man’s propensity to make or build. One need only glance at one of the world’s greatest cities, say Manhattan, to be impressed with the size, scale, and variety of construction that is present. But construction is not unique to Man as a variety of insects, for example termites, build elaborate communal living structures. And generative AI often returns structures far more elaborate than envisioned by most of the world’s architects (Gaudi not withstanding).

Others have argued that language and communication are what separate Man but then what does one do with gorilla communication or parrots who clearly ‘talk’? And where does ChatGPT’s dialogs and replies fit into this schema?

The ability to reason is often proffered as a possibility and the impressive amount of reasoning that has been produced, particularly in the fields of the science and mathematics, seems to reflect the unique nature of Man. But at Peter Kreeft points out in his lectures entitled Ethics: A History of Moral Thought, beasts also show a degree of reasoning. He cites an example of a dog pursuing a hare who comes to a three-fold fork in the road. After sniffing two of the trails with no success, the dog immediately pursues the hare down the third without bothering to sniff. And, of course, expert systems and symbolic logic programs have been ‘reasoning’ for years and remain important components in many fields.

The list could go on, but the point should already be clear. Much like one of Plato’s Socratic dialogs, this argument over what separates Man from the other autonomous agents that inhabit the world around him (beasts and AI) is not easy to resolve. Clearly there is some character in Man that sets him apart as he seems to be the only entity that exhibits the ability in the material world to make moral judgements based on The Good, The True, and The Beautiful but distilling what that ability is remains elusive.

This elusive, ineffable nature of man is symbolized in Eco’s arguments in The Name of the Rose by the continued debate within the monastic community over the nature of laughter. The following snippet of dialog between Jorge of Burgos and William of Baskerville give a flavor of that debate:

“Baths are a good thing,” Jorge said, “and Aquinas himself advises them for dispelling sadness, which can be a bad passion when it is not addressed to an evil that can be dispelled through boldness. Baths restore the balance of the humors. Laughter shakes the body, distorts the features of the face, makes man similar to the monkey.”

“Monkeys do not laugh; laughter is proper to man, it is a sign of his rationality,” William said.

“Speech is also a sign of human rationality, and with speech a man can blaspheme against God. Not everything that is proper to man is necessarily good.”

Wrestling with this question is by no means restricted to ‘high-browed’, historic fiction. Consider the following snippet from Guardian of Piri episode of Space 1999 (aired Nov of 1975) wherein Commander Konig gives his own answer for what sets man apart.

Clearly, we recognize that there is something innately special about Man even if we can’t nail down what precisely what that means. The debate surrounding this point, which has no doubt existed as long as Man himself has had the self-awareness to wonder about his own nature, is likely to continue for as long Man lasts.