Building on the spirit of whimsy that has been lurking in these columns of late, I thought I would devote one last post to the ambiguities and philosophical twists in natural language. Not only do these curiosities shed light on the nature of human thought and speech, they also set a standard for any candidate trying to pass the Turing test. After all, a human response to certain phrases should sometimes be blank confusion or a dumbfounded response like “Sorry, but I don’t have a clue what you mean.” Other times, subtlety, irony, or humor – all decidedly human expressions – should result when a nuance in language, pointing to an elusive connection, a peculiarity of ideas, or an absurd notion present in a phrase we all take for granted, comes to the front.

The linguistic hedge will be our starting point. The concept of a linguistic hedge (caution: this Wikipedia link, while containing some useful examples, is full of modern mangling of the language such as using “they” instead of “he” and using passive instead of active voice) is a commonplace and useful component of language that we all use, even if the phrase is unfamiliar. Suppose you pose the question, “How hungry are you?” to a friend, and his response is, “Very hungry!”; you know that he wants some food fairly badly. The word “very” is one of the most basic hedges and fuzzy logic often employees it as a mathematical modifier to set membership (maybe more on this in a later post).

People use hedging in a variety of ways, to emphasize degree (as in “very hungry”, or “very, very hungry”), to dodge the truth (as in “to the best of my knowledge”), and to be sarcastic (“she is very good”). But few uses are as amusing as the use of the word “pretty.”

Ordinarily, English speakers use “pretty” as an adjective, with the typical practice being exemplified by sentences such as “She looks pretty,” or “She looks very pretty.” However, it is fairly common, in more slang-oriented speech, to say something like “John asked, ‘How big was the rock that you hit with your car?’ Steve answered ‘It was pretty big.’”

Google’s dictionary defines pretty (adverb) as:

adverb INFORMAL

adverb: pretty

- to a moderately high degree; fairly.

“he looked pretty fit for his age”

synonyms: quite, rather, somewhat, fairly, reasonably, comparatively, relatively

“a pretty large sum”

Just how does “pretty” turn into a linguistic hedge is a mystery (at least to me) but its use can lead to some very awkward and very funny constructions. One construction, filled with cleverness and mirth, is the use of pretty to modify words that common speech would normally consider antithetical to the adjectival use of pretty.

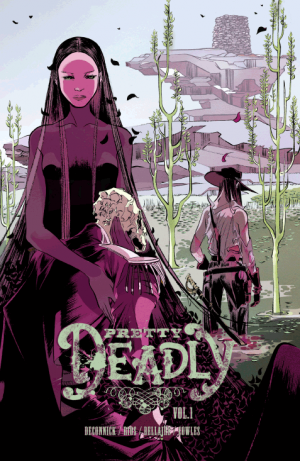

For example, there is a comic book published by Image comics called Pretty Deadly. The book centers on Jenny, the daughter of the embodiment of Death, who is both beautiful and a nearly unstoppable assassin.

An artificial intelligence capable of human-like responses would have to appreciate and, perhaps savor, the double meaning contained in the title, to allow itself to move back and forth between the two separate meanings, to imagine and possibly construct new associations inspired by the juxtaposition of two otherwise dissimilar words.

Likewise, to match its biological counterparts, it would have to enjoy the most humorous use of pretty when it modifies adjectives that are exactly opposite to its adjectival form, such as hideous, grotesque, repulsive, and so on. Consider the following set of man’s best friends

and the fully natural way in which they are labeled. Imagine an artificial intelligence trying to properly understand why “pretty ugly” or “pretty repulsive” is linguistically intelligible but why “pretty pretty” is just plain wrong. Of course, one can always program the AI to work around “pretty pretty” as a corner case but take a moment to reflect on who programmed us to recognize just how bad it sounds. Your answer should have been no one, because we just innately recognize just how stupid that phrase is.

Somehow, a true AI would need to learn and know and imagine how to use linguistic hedges to sound clever or funny or poetic without some vast if-then-else loop or training on large amounts of data that someone else blessed as proper speech. It should know when to honor the rules and when to break them and when to invent new ones. But such an AI is nowhere to be seen on the horizon, and that’s pretty sad.