English is a notoriously difficult language to spell and pronounce. If it challenges the organic learners ability to grasp and communicate it more than doubly so is a source of frustration for the programmer trying to teach bits of silicon, metal, and plastic to appear that they speak naturally.

A famous demonstration of the problems readily encountered in today’s lingua franca, attributed to William Ollier Jr., is the spelling of fish as “ghoti”. The proper pronunciation of this awkward looking sequence of letters strikes many people as something like “goatey”, an adjective that could be used to describe a thing with the essence or behavior of a the goat. But Ollier argues for the fish phonetic as follows:

- the letters ‘gh’ are to be pronounced as they are in the word enough

- the letter ‘o’ is to be pronounced as it is in the word women

- the letters ‘ti’ is to be pronounced as it is in the word nation.

Short, simple, and eminently confusing!

Ollier’s first donor word comes from a delightfully ridiculous family of words all sporting the ‘ough’ combination of letters and all having subtly or radically different pronunciations. Consider the following list:

- bough – a part of a tree; pronounced as [bou]

- bought – the past tense of to buy; pronounce as [bôt]

- cough – an action of the mouth and lungs; pronounced as [käf]

- dough – a mixture of water and flour used in baking; pronounced as [dō]

- enough – just the right amount of a required thing; pronounced [iˈnəf]

- through – to past into and beyond; pronounced [THro͞o]

This list contains six distinct pronunciations for the same four letter combination, representing an astonishing gain of nearly two distinct pronunciations per letter, most likely the greatest variability in the English language, possibly the world. And it is by no means exhaustive (even if putting it together exhausted the writer). And there are a host of other ‘ough’ words that didn’t make onto the list simply because they offered nothing new.

For example, consider that fought, ought, sought, thought all rhyme with bought and bring nothing new to the list even if they bring headaches to people learning the English tongue. Similarly, ‘ough’ in drought sounds the same as it does in bough despite the fact that trees need water (or perhaps because of it). Likewise, though’s similarity to dough consigns it to a mere mention in this paragraph rather than a place of honor (or is it shame) within the bullets above. And it is tough that tough and rough weren’t unique enough to make the cut.

But perhaps the most interesting no-show on the list is slough. This word is two-faced having two quite different sounds depending on whether it is a noun or a verb:

- slough – a swamp or mire; pronounced [slou, slo͞o]

- slough – to shed or cast off; pronounced [sləf]

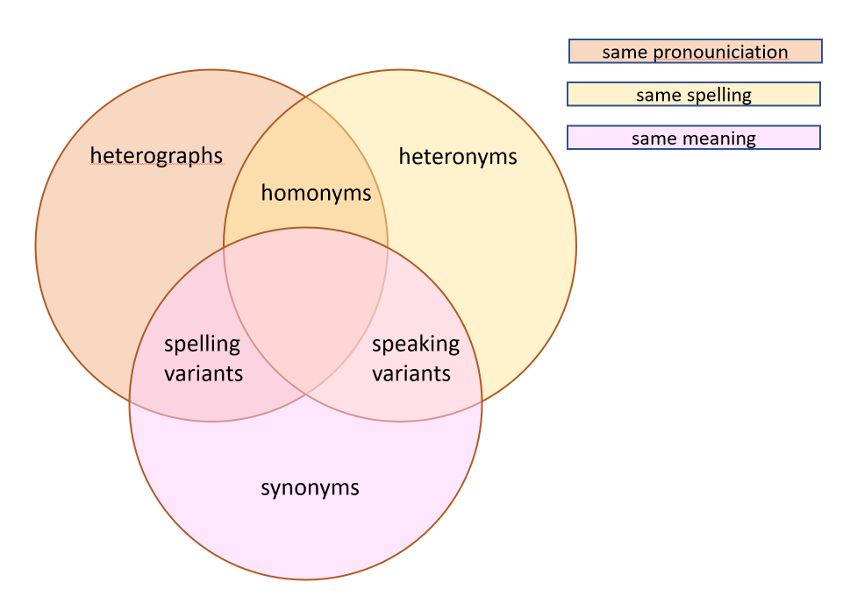

This example is, by no means unique. English is just brimming with curious words that lie in wait trying to trick the speaker. There are the heterographs that have the same pronunciation but have different spellings and meanings. A particularly sinister example is the set of to, too, and two. There are the homonyms that share both the same pronunciation and spelling but also mean different things. The clause, the rose rose to glory in the garbage dump, is a fine example. Together the heterographs and the homonyms form the set of homophones; words that are pronounced the same but which mean different things (regardless of spelling). Homonyms are also often called homographs, thus serving to bring us to the next category, the synonyms; words with different spellings and pronunciations but which have the same meaning. Two closely related categories that seem to have no official designation are the spelling variants and the speaking variants. Into the latter go all those weird words like color and colour, saber and sabre, and normalize and normalise. In the latter category, one finds words like often, in which the speaker may include or omit the ‘t’ sound.

All of these categories can cause problems to speakers, natural and artificial though they may be. But no category seems to engender as much confusion and consternation as the heteronyms. Some of the classic examples that fall into this category are:

- bass the musical instrument ([bās]) and bass the fish ([bas])

- minute the unit of time ([ˈminit]) and minute adjective describing size ([mīˈn(y)o͞ot])

Together the heteronyms and homonyms make up the homographs; words with different meanings but the same spelling (regardless of pronunciation). The following Venn diagram (based on the one in the Wikipedia references) helps one keep score.

Heteronyms are particularly problematic for computer-generated readings of the written word because context changes the pronunciation and meaning in a way that seems hard to find solid rules that work in all instances.

Consider the ridiculous sentence:

Both instances of bass are nouns but it seems clear that the musical instrument can’t be the subject of any sentence, so maybe a programmer can write a rule to accounted for this case or, since it is unlikely that the previous sentence will show up in anything worth writing specialized code to handle, maybe it is ignored altogether.

The sentence:

may be an entirely different story. There is a reasonable chance that a sentence containing both the noun and adjective form of minute will be written and the word order in the sentence is unlikely to indicate which is which in nearly all cases. Still the local association of the article a just before the noun form and the occurrence of the noun fraction just after the adjective form may be enough of a pattern to write a rule.

And then there are the voluminous list of noun-verb heteronyms, a sample of which are listed here (for a full list of two-syllable examples):

- Address and address

- Bow and bow

- Buffet and buffet

- Desert and desert

- Dove and dove

- Lead and lead

- Present and present

- Project and project

- Row and row

- Slough and slough

- Tear and tear

- Wind and wind

Writing rules for a machine to naturally speak any sentence with any of these is difficult. In some cases the word order makes it easier. For example:

guarantees that the subject (he) will be followed by the verb form of bow rather than the noun form.

But other sentences are not so obvious. Consider these sentences involving the very treacherous word tear, which is a sort of palindrome of noun-verb heteronyms since the [ter] and the [tir] form can be both a noun and a verb.

and

Definitely more difficult, but perhaps doable by scanning the sentence for the helper verbs like will and to.

But the fun doesn’t stop there. Consider the following command.

Is this a command telling an unidentified person to hand over where he lives or to give a speech to an audience. There is simply no way of knowing without comprehending the rest of sentences around it.

And there you have, a brief but bewildering dip into what makes learning English a tricky enterprise. A relatively small set of rules may cover a majority of sentences encountered but to get to fluency an enormous number of special cases and exceptions must be mastered, some of which required a non-local analysis of the text to ensure correctness. And while teaching a machine to read and speak English aloud is definitely a noble goal for the computer scientist (and especially beneficial for the seeing-impaired) it is one that is likely to come with a whole host of frustrations for year to come. It amazing that any of us can communicate with each other at all.