Last month we started on a journey to explore and experiment with the computer algebra system SymPy that is freely available in the Python ecosystem. The aim is to create, within this package, a rule system that implements the basic transformations and identities of the Fourier Transform. But the goal is very loose and a great deal of emphasis is placed on the journey more so than the final product. To this end, there are three focus areas: 1) working out the steps needed to manipulate symbolic expressions, 2) looking at what an intelligent agent would need to do as a way of exploring more artificial intelligence, and 3) discovering how the human does these steps differently and, in the process, having some new found appreciation for the subtleties and brilliance of the human mind.

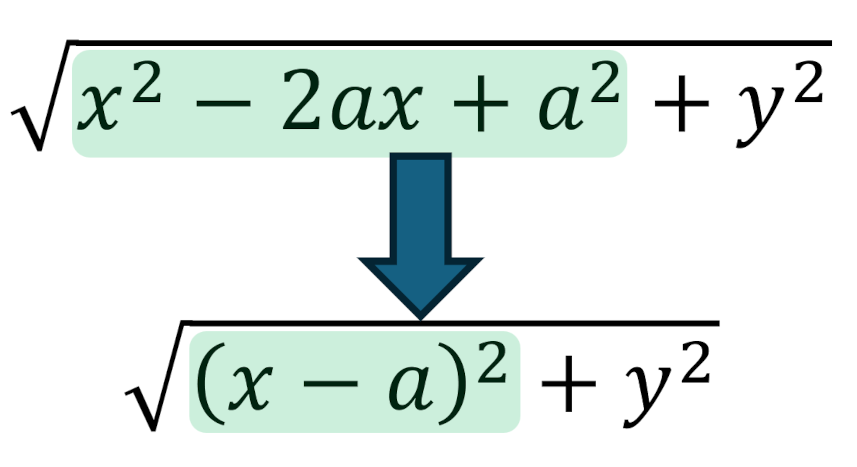

To start, we look at a classic algebraic manipulation that comes up often in the study of all sorts of disciplines ranging from computer graphics, to gravity and electromagnetism, to geometry and trigonometry – namely the application of the Pythagorean theorem to find the distance or magnitude of a vector by computing the square root of the sum of the squares.

To keep things notationally simple, we’ll consider the very simple expression:

\[ D = \sqrt{ (x-a)^2 + y^2 } \; \]

made up of the symbols $\{a,x,y\}$.

In a variety of settings, society ‘expects’ that competent students of algebra to either recognize or, at a minimum, be able to verify that

\[ D’ = \sqrt{ x^2 – 2 a x + a^2 + y^2} \; \]

is ‘equal’ to $D$.

Of course, the word ‘equal’ very elastic and, as a result, it isn’t precise enough for either deep exploration of the human mind or for the shallow, do-as-I-am-told workings for a computer. Let’s try to nail that down with some better definitions.

First, let’s define the term mathematically equal to contain the meaning that a teacher wants to convey when he says that $D=D’$. Mathematical equality means that for every choice of values for $\{a,x,y\}$ the numerical result obtained by substitution from $D$ is exactly the same as the numerical result obtained from $D’$ by the same process.

Now let’s define the term structurally equal to mean that the formal way the symbols are written in the expression are the same even if the identity of the symbols are not. For example,

\[ D’’ = \sqrt{ (q-q_0)^2 + p^2 } \; \]

is structurally equal to the expression for $D$ since we recognize that the symbol substitutions

\[ x \rightarrow q \; ,\]

\[ a \rightarrow q_0 \; , \]

and

\[ y \rightarrow p \; \]

make $D$ look the same on paper as $D’’$. Note that two expressions that are structurally equal need not be mathematically equal if assumptions about the different symbols aren’t the same. For example, if $x \in (-\infty,\infty)$ but we restrict $p \in [0,\infty]$, then, despite their structurally equality $D$ is not mathematically equal to $D’’$ when $x < 0$.

We will use the term exactly equal to mean that two expressions are both mathematical equal and structurally equal and have the same symbols.

These three definitions have holes and limitations. The holes are a by-product of limitations of human logic and we won’t try to patch them so much as work around them when the time comes. Regarding the limitations, we can give a general notion of where they will show up and then revisit them in the future. The primary limitation(s) is that the notion of equivalency is left out. To give a flavor of this consider the two expressions

\[ \frac{d}{dx} \left( x^2 – 3 a x + 9 \right) \; \]

and

\[ 2x -3a \; .\]

These two expressions are neither mathematically equal (one can’t simply substitute in a value for $x$ before taking the derivative) nor structurally equal (the symbol structure isn’t the same). But they are equivalent in the sense that applying the derivative in the first leads one to the second. And, there is another wrinkle when considering moving from the second expression to the first, in that $2x – 3a$ is equivalent to an infinite number of expressions of the form

\[ \frac{d}{dx} \left( x^2 – 3 a x + constant \right) \; .\]

Since we will have our hand full just dealing with how to teach an agent how to determine if $D$ is structurally or mathematically equal to $D’$, we will defer these deeper matters and look at a simple example from basic physics.

It is typical for a professor, when teaching say electromagnetism, to look at $D’$ and simply highlight the first three terms under the radical and say something to the effect that the form a perfect square which can be ‘reduced’ or ‘simplified’ to the other.

However, there is no cognitive mind behind a computer (no matter how much training data it may have ingested) and so it can’t fill in the gaps and move (albeit not usually effortlessly) between the various ambiguities and elastic meanings in the way a human can.

To understand this point better, consider that to represent the expression above requires nesting $x^2 – 2 a x + a^2 + y^2$ under a square root symbol. That’s four terms ‘owned’ by the square root, which we wish to ‘factor’ into two terms $(x-a)^2 + y^2$. In addition, each of these terms is complicated as none are ‘atomic’. A term is atomic if it consists of a symbol and nothing else.

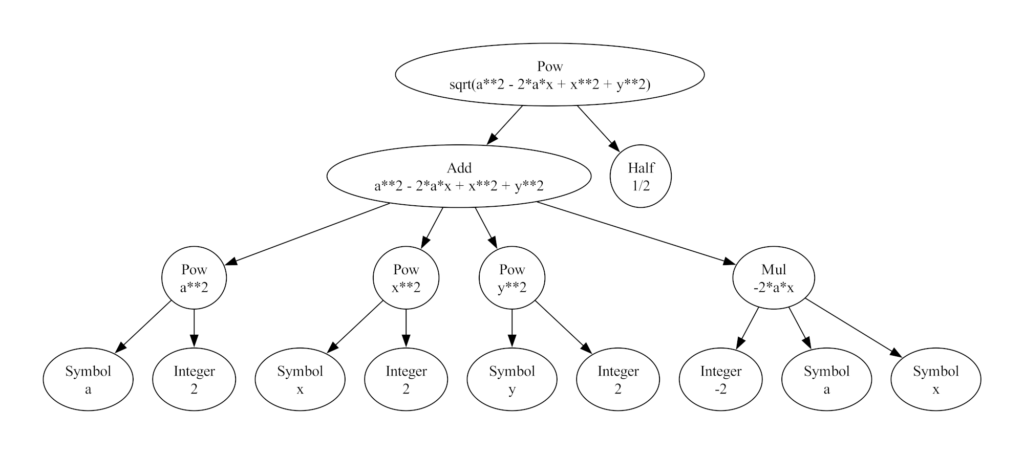

Driving this point home is easier done with a visual. Using the graphviz application and the corresponding Python API, we can visually display how these various expressions are represented internally. SymPy uses a tree structure that, for the expression $D’$, looks like

Every node in the a SymPy tree is either a function or a symbol. Functions own (almost always) children nodes reflecting their composite. Symbols are terminal nodes reflecting their atomic nature. At the top of the tree is the Pow function (for power) with two main branches: Add and Half. Add is the function that owns the four terms that algebraically add together while Half is a special symbol meaning 1/2. SymPy reserves a special symbol for this since division by 2 is so common. Of the four main branches of Add, three are Pow and one is Mul (for multiply). Like Add, Mul can own an arbitrary number of branches. In this case there are three, each terminating with the symbols $-2$, $a$, and $x$.

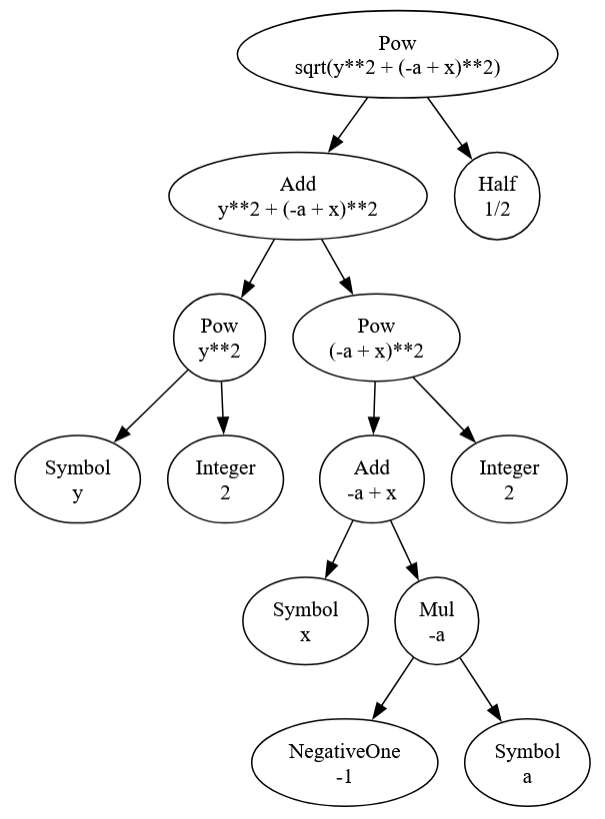

In order to manipulate the only some of the contents under the square root we must be able to find that portion of the tree that corresponds to $x^2 – 2 a x + a^2$, remove it, manipulate it, and then return the new structure to the tree so that it looks like:

Getting the contents of the square root is relatively simple: we simple ask for the arguments of the expression and we get a tuple containing the Add branch and the Half Symbol.

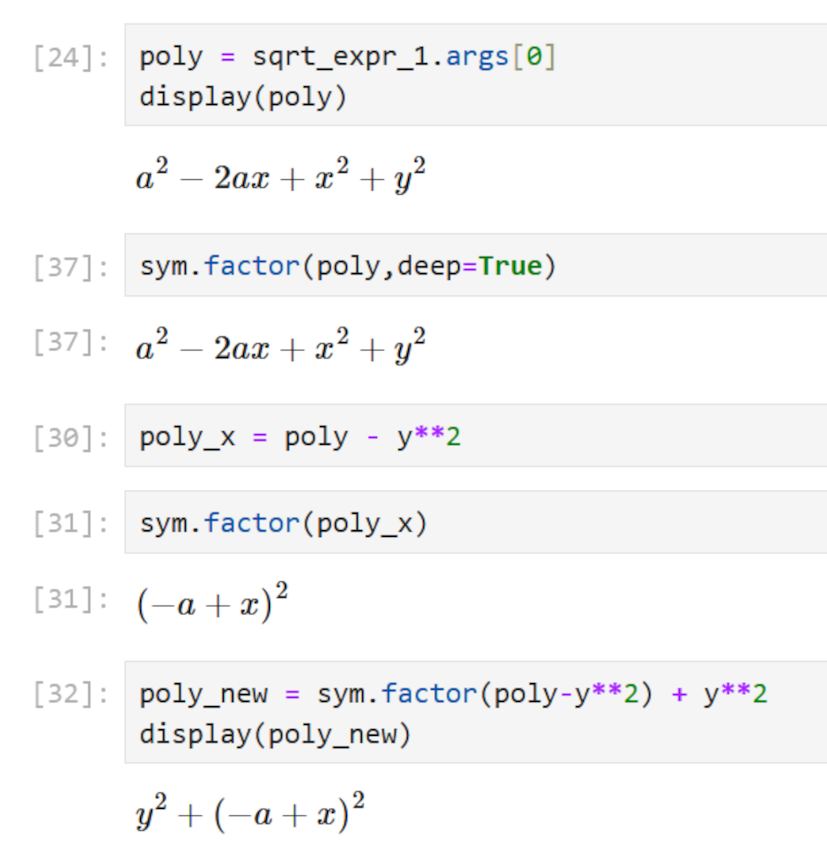

The Add branch is now a polynomial expression that we might be tempted to try SymPy’s factor on. However, Factor doesn’t know what to do with the portion involving $y^2$. However, if we isolate the portion of the expression involving just $x$ and $a$ by subtracting off the $y^2$ piece, factoring, and then adding $y^2$ back, we get a reasonable result. Both of these approaches are shone in the notebook snippet below:

This behavior is not unique to either this situation nor to SymPy. Asking Wolfram Alpha to factor $x^2 -2 a x + a^2$ works fine but asking it to perform the same function on $x^2 -2ax + a^2 + y^2$ doesn’t give an acceptable answer (although its answer differs from SymPy’s default but coincides with SymPy being directed to factor of the field of the reals).

Two final points. First, there is an algorithmic way of doing the separation of the polynomial into a $a$-$x$ part and a remainder that can be run without as much hand-holding as this snippet shows:

a, x, y = sym.symbols(‘a x y') poly = x**2 - 2*a*x + a**2 + y**2 ax_part = sum( term for term in expr.as_ordered_terms() if term.has(a, x) and not term.has(y) ) rest = poly - ax_part sym.factor(ax_part) + rest

Second, and far more important. Just for fun, I asked Chat GPT to factor $x^2 -2 a x + a^2 + y^2$ both absent from and under the square root and it delivered the ‘professorial’ answer $(x-a)^2 + y^2$ in either case. It was also able to factor a more difficult SymPy example of $2x^5 + 2x^4y + 4x^3 + 4x^2y + 2x + 2y + a$ into $2(x+y)(x^2 + 1)^2 + a$ even though both Wolfram Alpha and Sympy could not out of the box. I suspect the reasons for these successes are either that these are well-known examples that reside somewhere within its system or it knows how to make these systems work better than I do. The next logical question is then why are SymPy and Mathematica not out of business. I think the only answer to this is that these success are superficial. That real mathematical creativity is still beyond the capabilities of the machine. But, I suppose, time will tell.