There has been a lot of commentary floating around about the recent ‘summoning a demon’ remarks of by Elon Musk on the dangers of artificial intelligence.

Mr. Musk may be an excellent entrepreneur but his philosophical arts are clearly lacking. Human intelligence has an intrinsic capacity that AI practitioners have yet to capture. This intrinsic capacity is best demonstrated by considering how humans learn their language.

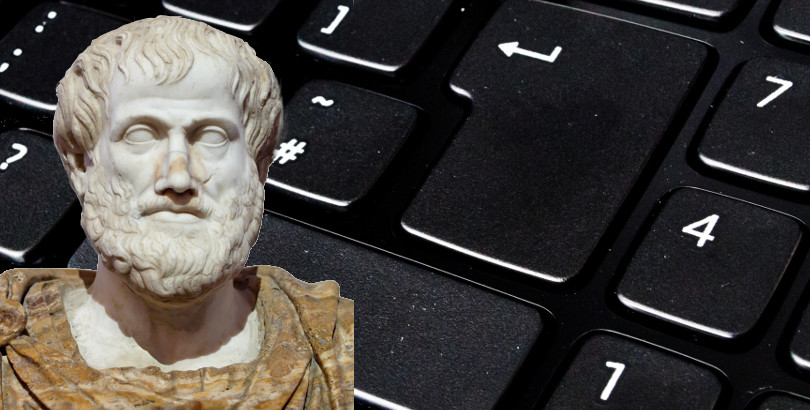

Consider the following images of four fairly common objects: 1) an ordinary magnifying glass, 2) an empty water glass, 3) a water bottle with a magenta filter, and 4) a magenta USB drive.

Now imagine that you are about to travel to another country where you don’t speak the native language. You’ve made arrangements to travel on Monday with your interpreter arriving a day later. You pack your bag, making sure to include the four objects shown above (not as strange as it sounds – I routinely travel with three of them).

Due to a strike that happens a few hours after you arrive you become stranded in the country without your interpreter and with no immediate way home. Having nothing better to do you try your hand at learning the language.

You open your bag and pull out the four objects shown above. After a brief pantomime where you open and close your jaw and make sounds in English, one of the native speakers gets the notion that you want to learn some of their mother tongue. Now the fun begins.

The native points at the bottle and says “zerk”. What does this mean? There are many possibilities. He might be saying their word for “container”, or “clear”, or “plastic”, or “water”, or “magenta” or etc. You hope he means “container” and you point at the glass and say “zerk”. He then shakes his head and says “quig”. What does that mean? Maybe it means “empty”, or “glass”, or “clear”, or maybe even “container “.

You open the water bottle and pour all of the water into the glass. Your ad hoc teacher now points at the glass and says “zerk”. Inspired, you then pour some water into your hand, look at him expectantly, and then say “zerk”. Happy that you are now getting the idea, he nods his head vigorously, smiles broadly and says “zerk!” Congratulations you’ve now learned your first word in his language.

Let’s step back for a minute and discuss how you likely put together the concept of water with the sound “zerk”. It was unlikely that for the first attempt at teaching you his language, that your friend would say the word for an accidental associated with the bottle and would focus on the essentials instead. The problem is identifying which properties were essential and which were accidental and then determining which of the hopefully smaller set of essential properties was meant by “zerk”. Somehow you recognized or assumed (implicitly) that an essential property of your interaction with him would be to focus on the essential properties of the objects in question. You also assume that both of you possess a similar way of perceiving the world and culturally categorizing it. Basically, you have an abundance of clues to help you put things together. You also have a capacity to separate out essential properties from accidental ones, so that if the color of the liquid in the bottle were different, or the filter were missing, the bottle would remain a bottle conceptually (even if it looks different).

Now instead of a traveler to an antique land, you are a newborn. Someone is saying “doht” and is pointing at the USB key. What do they mean? How many repetitions and cross-references do you go through in order to figure out what it means? As a newborn, you don’t have the contextual and logical clues that helped you as they did in the foreign travel scenario. But you do have an innate capacity to apprehend the world. Whether it takes a hundred or a thousand attempts, after enough pointing back and forth between the USB key and the bottle, it suddenly hits that “doht” means magenta.

It probably takes longer to realize that a common property shared by the magnifying glass, the drinking glass and the bottle is the property of “clear”. Is this property an essential or accidental property? Most of us would answer it is essential for a magnifying glass to be clear but an accident if the bottle and the drinking glass are clear. So how can any of us learn what clear means when sometimes it falls into one category and sometimes into the other?

I don’t know. I do know that somehow we all can do it. I can’t explain it and I don’t quite know how to describe it any more than I daresay anyone else does, but I know it exists because I witness it.

Now let’s return to the comments of Mr. Musk. It is a sweepingly generous statement to say that our AI efforts have been even primitive successes. As a science, we do not understand this world-apprehending capacity that each of us is equipped with, in firm-ware, as we emerge from the womb. We know we have it but we have yet to codify it let alone translate it into something a computer can emulate. And even if we could, how do we give the machine all the contextual cues and clues that we take for granted in our interactions with our fellow humans. Sometimes I doubt we ever will succeed but for sake of argument I won’t press the point.

What I do know is that we are decades or centuries away from having this capability shared by the silicon and plastic companions that accompany us in our modern life. No Matrix, or Skynet, or Demon Seed is just around the corner, ready to burst out of the pentagram to which we attempt to confine it. No man-made machine with sinister or sublime intelligence is ready to sway our world – except for the man-made machines we manufacture through the tried–and-true method of making babies.

One last word is in order. Print out the four pictures featured here in the post, make up some novel sounds for things like “clear”, “small”, “shiny”, and the like, and see how long it takes for a friend to guess. Then give them a turn. It’s actually fun.