I recently had a chance to read Socrates Meets Machiavelli: The Father of Philosophy Cross-Examines the Author of the Prince, by Peter Kreeft. Kreeft is a faculty member in the Department of a Philosophy, Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences, at Boston College. He is well-known as a Christian Apologist and, by his own words, is a teacher and not a great philosopher. Nonetheless, I’ve found many of his works to thought provoking and well-argued as any good philosopher should do. Even when I don’t agree with his conclusions I can see how he got from point A to point B why he would lean the way he did.

In Socrates Meets Machiavelli, Kreeft attempts to make a modern-day Socratic dialog out of an imaginary meeting between the two titular characters in some limbo after both have died. The work is intellectually stimulating but ultimately it fails at achieving the form and function of its more celebrated predecessors. Even though Kreeft’s writing is not as poetic or skilled as Plato’s, the reason for this dialog falling far short is that there is a sense that Kreeft has his thumb on the scale from the start when the two characters meet.

To understand this point, consider Plato’s classic work The Euthyphro, in which Socrates meets up with the title character outside the Athenian courthouse. Socrates is there to face the charges that would lead to his death. In contrast, Euthyphro is there to accuse, not to rebut an accusation. Both are Athenian citizens meeting on common ground. Yes, Socrates is clearly the smarter of the two and he is far more artful in demonstrating the holes in Euthyphro’s arguments than the latter is in filling them. Despite that, Socrates doesn’t win in the dialog – he simply succeeds in pointing out that the truth is far more elusive than Euthyphro would like to believe.

From the start, the meeting between Socrates and Machiavelli is of a different cast. Consider the following exchange about 4 pages in

Socrates Correct again.

Machiavelli: So is this Heaven of Purgatory?

Socrates It is Purgatory for you and Heaven for me.

Machiavelli: How can that be?

Socrates It is for me a continuation of the most heavenly task I knew on earth: to inquire of the great sages, to pursue wisdom from those who know. For they are the opposite of myself, who do not know. And it will be Purgatory for you as it was to my fellow citizens of earth. But here no one has the power to give the gadfly a swat and send him away to the next world. You must endure my questions.

Machiavelli: So you are my torturer.

Socrates No, I am your friend.

Machiavelli: My inquisitor.

Socrates No, your teacher.

Machiavelli: By means of inquisition.

Socrates No, by means of inquiry. The unexamined life is not worth living, you know.

From this early stage Kreeft establishes the position of authority and power of Socrates over Machiavelli. As a result, the entire work feels more like a polemic and less like a pursuit of truth; more of a monologue by Socrates to teach Machiavelli the error of his ways rather than a dialog in which both separate error from fact.

Nonetheless, the book is well worth reading if for no other reason than the structured approach that Kreeft’s uses to analyze philosophy and ethics and the strong conclusions that follow from its use. In the interest of full disclosure, I am self-taught in my philosophical pursuits so, to the professional (which Kreeft, in his lecture course Ethics: A History of Moral Thought, points out is a bit like being an intellectual whore), maybe the following point is pedantic. Still I will pluck up some courage and put it forward.

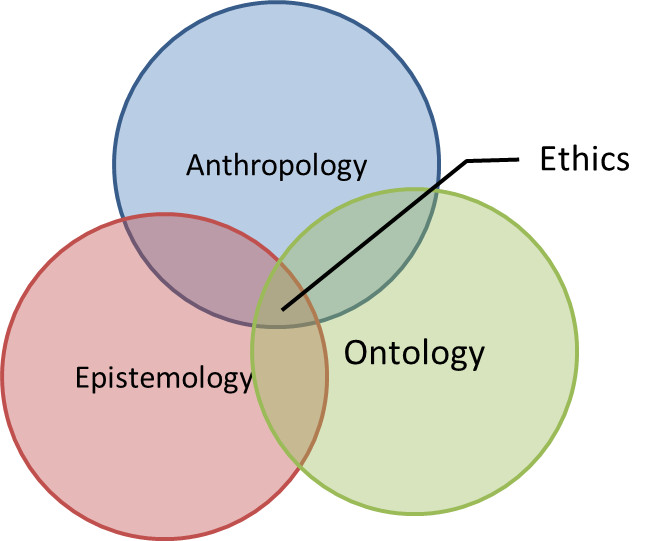

Until digesting Kreeft, I had looked at the fundamental base of philosophy to be built from ontology (the study of what the world is or the study of being) and epistemology (the study of what can be known). Kreeft makes a subtle but powerful division of ontology into two pieces: anthropology, here defined to be the study of the human being; and ontology, defined to be the study of the being of what remains. Ethics then finds itself at the intersection.

Of course, divisions of these sorts are artificial in that how we know what we know and why we know it is as much a function of who we are as people as it is a function of what is out there to be known. This division is not unlike the quantum mechanical division between system, environment, and observer. All are made from the physical world and are inextricably linked and yet it is useful to draw boundaries in order to understand.

And understanding is the great reward that comes from reading Socrates Meets Machiavelli. No matter where one stands on the ethics questions raised in the text or whether one agrees with Kreeft, there is no denying that he makes a powerful argument that the practical man is a philosophical man. That there is simply no way to succeed in the here-and-now without first deciding on firm meta-physical principles and then applying them is a central message; a message that makes one’s investment with this book worthwhile.