In the last post we discussed the epistimological divisions in philosophy between a priori and a posteriori knowledge and the divisions due to Kant between the notions of analytic and synthetic statements. As a brief reminder, a priori knowledge stems from first principles and can be understood using the human capacity to grasp the essential nature of things. A posteriori knowledge is obtained only after examining a thing and coming to a conclusion about its nature – a conclusion that cannot be grasped by reason alone. An analytic statement is one which is true and in which the subject contains the predicate (that is to loosely say that one defines the other) while a synthetic statement is one that is neither false nor is analytic.

On the surface there seems to be such a strong tie between a priori knowledge and analytic statements, on one hand, and between a posteriori knowledge and synthetic statements, on the other, that there is a temptation to equate the two concepts in each case. Thus one might want to say that all statements of a priori knowledge are analytic and all statements of a posteriori knowledge are synthetic.

But as is usually the case with logic when examined very carefully, ideas that seem rock-solid based on a casual examination become a lot more uncertain when looked at more thoroughly. However, these kinds of abstract examinations are often dry. So for this post we’ll try to apply these ideas to the popular medium of the murder mystery.

What should be said about the murder mystery? I think that if Aristotle were alive today one of his favorite past times would be reading and/or writing murder mysteries. This should come as no surprise since Aristotle is credited with formalizing logic and logic and solving mysteries go hand-in-hand. The murder mystery, or detective story as it also called (not all the crimes are murders – only the most enjoyable ones), are individual studies in epistemology. At its heart is the idea of pronouncing a statement of truth; of disclosing ‘whodunnit’.

Consider the analysis of G. K. Chesterton, one of the twentieth century’s most profound thinkers and prolific authors, who penned dozens of works on analysis, philosophy, and social criticism. Chesterton, who was home with logic and critical thinking in its many forms, was particularly fond of the detective story and wrote often about it. One of his notable observations was:

Rex Stout, the author of over 70 detective stories, had the following very nice description of the detecting process. Speaking about his gourmand and rotund detective Nero Wolfe, Archie Goodwin, Wolfe’s assistant, has this to say about his boss’s moments of genius:

If a detective story is an individual study in epistemology then it should be possible to examine each detective in terms of their where they fall in the division between a priori and a posteriori knowledge and between analytic and synthetic statements of truth. In this way, maybe we can shed some light on the thornier sides of this debate and also have some fun doing it.

Before examining some of the great literary detectives, let me state that none of them are purely one way or another. There is no author of detective fiction (at least not one I would want to read) who would believe that crime can be solved purely by thinking about the world from first principles nor who would believe that crime can be solved solely by the dry gathering of facts. It is the interplay between the two extremes that is the engine of discovery and truth detection. Nonetheless, each these detectives leans, as does the author who sits behind their adventures, more towards one extreme or another.

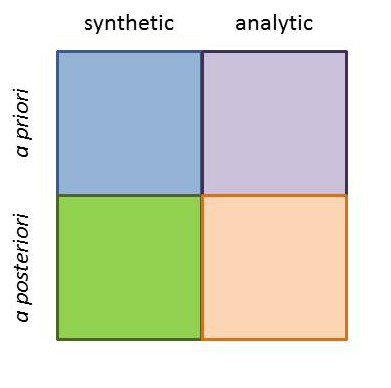

We can envision a categorization scheme for detectives where each is placed on a two-dimensional grid. To the left is the extreme of the synthetic and to the right the extreme of the analytic. At the bottom is a posteriori knowledge whereas at the top is a priori knowledge. An empty grid looks like

and placing a detective in the top right means that he depends more heavily on analytic a priori methods to solve crime than by other means.

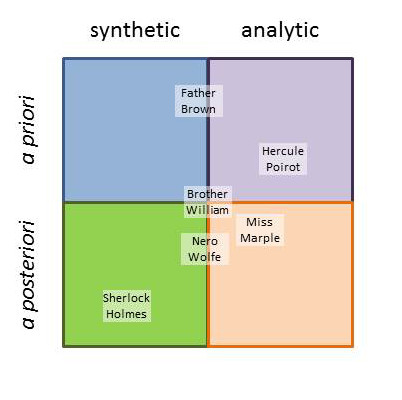

Our task is then to debate, and argue, and wrestle with where to place each. I won’t pretend to have a well-conceived and impregnable argument for what I present below. Rather I offer it as food for thought and, perhaps, the basis of some really enjoyable discussions with family and friends.

The easiest place of start is with Sherlock Holmes. For this discussion, I will be dealing only with Holmes in his original incarnation as conceived of by Since Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle and not some of the more modern adaptations. The sleuth of 221B Baker Street often solved the mysteries confronting him through observations correlated with dry or obscure facts. Red clay from a particular quarry in northern England combined with an encyclopedic knowledge of the British Rail time tables were a more common route to the solution than ponderings about human nature. Thus we can classify him as predominantly as synthetic and a posteriori.

The two famous creations of Agatha Christie, Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, are cut from a decidedly different cloth. Both of these sleuths depended heavily on their knowledge of human nature and often worked from motive to solution. Clearly they are both analytic, but it seems to me that Poirot starts more from well-articulated first principles and methodical deduction than his female counterpart. Poirot can explain exactly how he arrived at his conclusions (consider his ‘mentoring’ of Doctor Sheppard in the Murder of Roger Ackroyd) even if he often won’t and he needs only the bare facts to proceed (The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim). In contrast, Miss Marple relies on a lifetime spent examining human nature ‘under a microscope’ in her village of St. Mary Mead. As she explains in Sir Henry Clithering, her knowledge is akin to an Egyptologist who, due to a lifetime handling Egyptian scarabs, can tell when one is genuine while another is a cheap knockoff even if he can’t explain how. She often jumps to the solution and then gathers or reconciles facts only latter (Death by Drowning). Thus I would be inclined to place Poirot in the analytic and a priori sector and Miss Marple in just below him somewhat in the a posteriori square.

Nero Wolfe, already mentioned above, is more difficult to place. He seems to slide back and forth between the extremes, having the greater fluidity early on in Stout’s writing. In some cases, he is clearly synthetic in his approach. Consider Fer De Lance, where he asks a golf club salesman to demo how to swing a club to confirm his suspicions about the delivery method of a poison dart or The Rubber Band, where he realizes a connection between two usages of the word ‘rubber’ to impeach the murderer’s alibi. In other cases, including The Christmas Party and Death of a Doxy, he relies solely on his understanding of human nature and his ability to play upon a murderer’s irresistible compulsion to force a conviction. I place him nearly equally balanced between analytic and synthetic and tipping more towards a posteriori than a priori.

The final two detectives I’ll discuss both happen to be Roman Catholic priests: Father Brown the creation of G. K. Chesteron and Brother William of Baskerville from Umberto Eco’s brilliant novel The Name of the Rose. There is some irony here in that Chesterton was a devout catholic and Eco is a self-declared atheist. Nonetheless, both detectives depend on their training in philosophy (with particular emphasis on Thomas Aquinas) and the intellectual and theological traditions of the Catholic Church to find solutions to their mysteries. Father Brown is deeply logical and staunch defender of reason (The Blue Cross) but is prone to inspired deductions where, as Chesteron puts it (The Queer Feet):

In contrast, Brother William seems to take a more measured approach. On one hand he is quite proud and comfortable in his use of logic as in the affair of Brunellus the horse as he and Adso, his novice, approached the unnamed abbey where the bulk of the book is set. At other times, he seems to despair of ever knowing anything or, at least, anything with certainty as in his explanation to Adso of how he got the right answer using from the wrong approach. (An aside: the whole discussion associated with penetrating and navigating the labyrinth is delightful reading and worth studying).

All things considered, I tend to plop Father Brown down into that controversial region where synthetic a priori knowledge sits and I place Brother William firmly in the center.

My final diagram looks like:

Obviously, I’ve ignored a host of beloved literary detectives, including C. Auguste Dupin, Perry Mason, Ellery Queen, Lord Peter Wimesy, and Sam Spade. Leave a comment telling where on the diagram you placed your favorites and why.